This study seeks to provide an overview of current progress in the designation of national competent authorities, and to analyse how national governance architectures are being developed. The study shows that one week prior to the deadline, the majority of member states were behind schedule. Progress seems to have been fragmented, with many states not having made an announcement about their designation choices, or not legally enshrining their designation decisions. A few draft governance frameworks, some of them unofficial, were announced. These present a centralised architecture for notifying authorities, but a fragmented one for market surveillance, with most authorities already identified.

On 2 August 2025, European Union (EU) Member States (MSs) were expected to have designated or established their National Competent Authorities (NCAs) responsible for implementing and enforcing the Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 on Artificial Intelligence (AI Act) at national level, to comply with Article 70 of the AI Act.[1] However, one week prior the deadline the formal and definitive designation of these authorities had not yet been ratified by all MSs.

Since the AI Act came into force, a number of projects have been carried out to identify the designated NCAs.[2] [3] These projects have gradually brought to light disparities between MSs in terms of the maturity of the designation process, revealing delays or, at the very least, limited public communication regarding ongoing negotiations. This article contributes to previously-published studies, by expanding the discussion on how MSs form their national governance architectures.[4]

One week prior to the deadline, most MSs were behind schedule: 21 had not yet submitted a national implementation law and 13 had not announced the designation of their NCAs. The 14 governance architectures available at the time revealed a centralised approach to the designation of notifying authorities, but a more fragmented structure for market surveillance, and a reliance on pre-existing institutions rather than newly established authorities. Data protection authorities were also assigned responsibilities, primarily as market surveillance authorities, although some MSs chose to exclude them from their governance architectures.

This study begins by presenting the methodology used for compiling and analysing the various national implementation laws as well as the designations of NCAs, while also acknowledging the limitations inherent in this documentary research (1). It then introduces the dual-level governance architecture established by the AI Act and explains the division of competences and responsibilities between the different bodies at national and EU levels (2). The study then examines how MSs’ national governance architectures are structured, in order to identify trends, convergences and divergences. This final section addresses the delays observed in the designation of NCAs and the emerging governance architectures, which tend to be structured around multiple but pre-identified authorities (3).

1. METHODOLOGY.

This section outlines the methodology employed for the collection and compilation of national implementation laws and NCA designations (1.1) and their subsequent analysis (1.2) while highlighting the limitations of this documentary research (1.3).

1.1 Data collection.

The analysis is based on a preliminary survey of announced, proposed and designated NCAs, as well as national implementing laws, either currently being drafted or already adopted. Given that the analysis is limited to an overview of the authorities referred to in Article 70 of the AI Act, the scope of this study is restricted to notifying authorities, market surveillance authorities, and single points of contact.

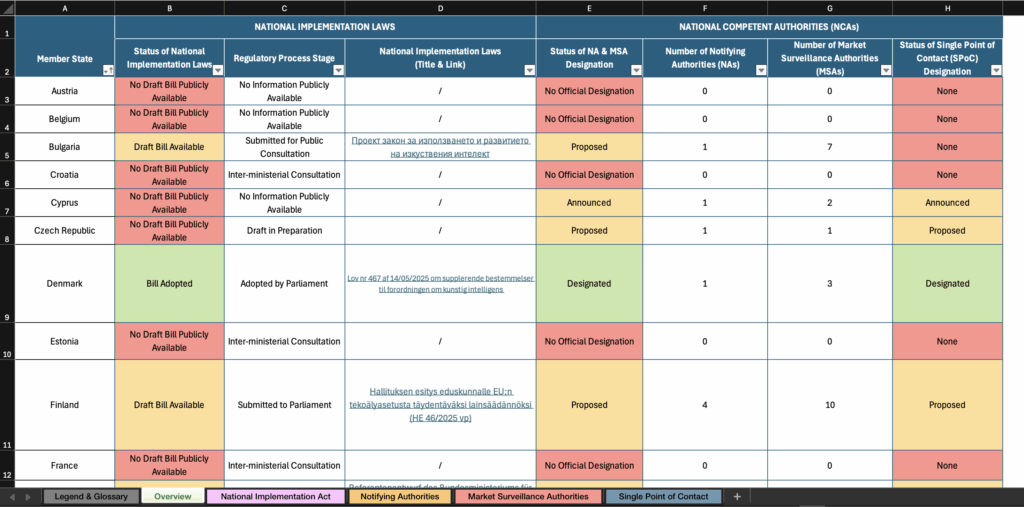

The data collection process involved documentary research of publicly available information online and a literature review based on the aforementioned pre-existing works. The data were retrieved from official websites (parliaments, governments or administrative entities) and specialised websites (press articles and legal blogs). The data collection period runs from February to July 2025. The data collected are presented in a table, current as of 23 July 2025 and available at AI-Regulation.com, with selected parts reproduced in the appendices.

1.2 Data analysis.

Based on these data, this study examines the formation of national AI governance architectures, focusing on the following parameters: the number of designated NCAs[5], data protection authorities designated as NCAs, and newly created authorities.

The section 3.2 of this study analyses the governance architectures of 14 MSs: Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Slovenia and Spain. These states were selected because their AI governance architectures were publicly accessible online as of 23 July and issued by official sources (government announcements, draft laws or reports). However, it is worth noting that although Bulgarian and German architectures have been included in the data set, they were not officially endorsed by their respective governments. In fact, the Bulgarian architecture was put forward by a minor party in the Bulgarian Parliament for public consultation, but it had not yet been submitted to Parliament as of that date. With respect to Germany, the document retrieved is not available on an official website and was drafted before the 2025 German federal election. Even though the projects outlined may not reflect the government’s final intentions, they shed light on a potential national approach.

Member states for which no public information was available as of 23 July have been deliberately left out from the analysis to simplify understanding. The states concerned are Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Estonia, France, Greece, Hungary[6], Malta[7], the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania[8], Slovakia and Sweden.

1.3 Limitations.

In order to contextualise the results presented, it is worth highlighting the methodological limitations that may have affected the accuracy of the analysis.

The first limitation concerns the accessibility of the documentation. The data obtained came from public sources, most of which were freely available. This limits the completeness of the information, particularly when no official designation had been published, or when discussions were held in confidential interministerial meetings.

The second limitation is the linguistic diversity of the media analysed. As many of the sites and documents were only available in the relevant national dialect, it was necessary to use automatic translation tools (Deepl Pro, Google Translation), which could affect the quality and accuracy of the translation.

Finally, the third limitation is our incomplete understanding of the specific national legislative processes of the 27 MSs, which can affect contextual understanding of certain national measures.

2. A DUAL-LEVEL AI GOVERNANCE ARCHITECTURE.

In order to ensure the effective implementation of the AI Act, Chapter VII establishes a two-level governance architecture: one at European level organised around the European Commission (2.1) and the other at national level, formed by MSs (2.2).

2.1 The European architecture formed by and around the European Commission.

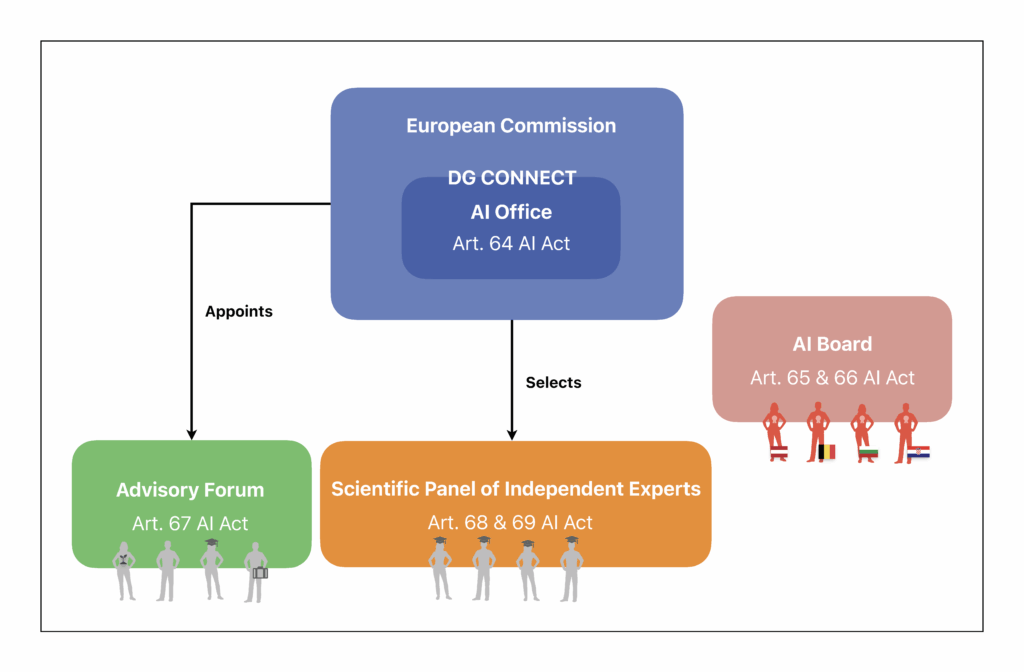

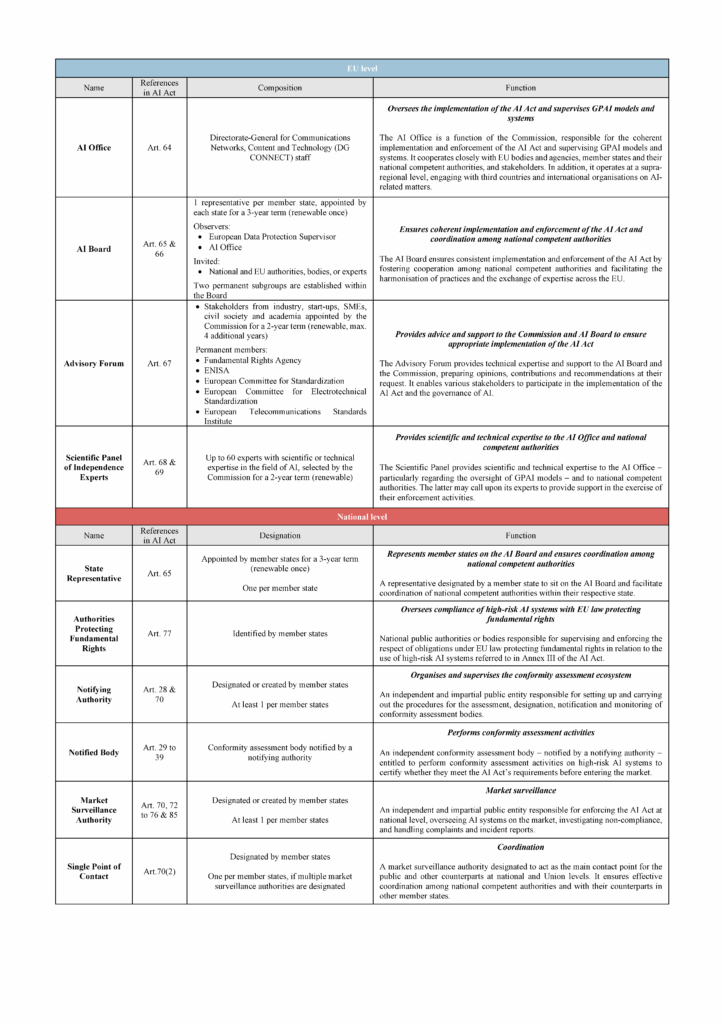

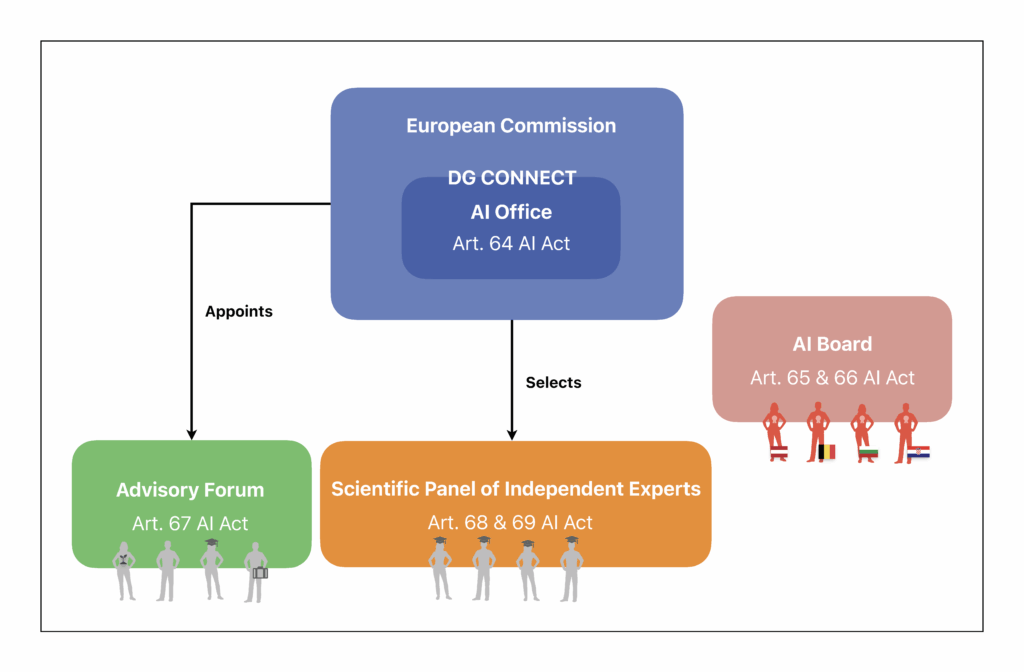

Section 1 of the Chapter VII (Art. 64 to 69) of the AI Act organises the AI governance architecture at EU level and settles four bodies: the AI Office, the AI Board, the Advisory Forum and the Scientific Panel of Independent Experts.[9]

These are new bodies that complement the existing entities concerned with digital regulation, some of which are expected to be consulted in accordance with the AI Act.

Chart 1 – AI governance architecture at EU level.

- The AI Office[10]

The AI Office is the European Commission’s (Commission) function responsible for overseeing the implementation of the AI Act across the EU and for supervising general-purpose AI (GPAI) models and systems.[11]

With regard to GPAI models and systems, the Office is tasked with developing tools and methodologies to assess such models and systems, monitoring the application of relevant rules and the emergence of unforeseen risks, and investigating potential infringements. As for the overall implementation of the AI Act, the Office assists the Commission in preparing implementing and delegated acts, as well as guidance documents and supporting tools.

It also supports the establishment and operation of AI regulatory sandboxes and coordinates the setup of the governance architecture at both EU and national levels.

The Office is part of the Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology (DG CONNECT) of the Commission, and it draws on DG CONNECT’s human resources.

Beyond its internal coordination role, the Office also has a supra-regional and international dimension, as it ensures cooperation not only with stakeholders, other Commission services, EU bodies, offices and agencies, and MSs authorities and bodies, but also with third countries and international organisations on AI-related matters.

- The AI Board[12]

The AI Board assists and advises the Commission and the MSs in ensuring the coherent implementation of the AI Act throughout the EU. It provides a forum for discussion among MSs to foster inter-state coordination and the exchange of best practices.

The Board is composed primarily of representatives from MSs, each of which is required to appoint one representative to serve a renewable three-year term. States representatives must have relevant competences and powers in their MS to actively contribute to the Board’s tasks, be designated as a single contact point for the Board, and be empowered to facilitate coordination between NCAs in their MS. State representatives are not merely representatives of their MSs, they shall be sufficiently empowered to carry out their responsibilities and enhance coordination effectively at the national level. In addition to states representatives, the AI Office and the European Data Protection Supervisor participate as observers, while other national or European authorities and experts may be invited to take part depending on the topics discussed.

The Board’s main tasks include supporting coordination among NCAs, promoting the exchange of expertise and best practices, contributing to the harmonisation of administrative practices, providing advice on the implementation of the AI Act – particularly regarding the enforcement of rules on GPAI models – issuing opinions on qualified alerts related to GPAI models, and assists MSs in the establishment and development of AI regulatory sandboxes.[13]

Two permanent sub-groups are established within the Board: one to serve as a platform for cooperation and exchange among market surveillance, and notifying authorities, and another for notified bodies. Additional sub-groups may be created, either temporarily or permanently, to address specific issues or tasks.

- The Advisory Forum[14]

The Advisory Forum is a consultative body that provides the Commission and the AI Board with technical expertise from a wide range of stakeholders on AI governance.

It issues opinions, recommendations, and written contributions upon request from the Commission or the AI Board.

The Forum is composed of representatives from industry, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and start-ups, as well as from civil and academia, all appointed by the Commission for a renewable two-year term. Its composition ensures a balanced representation of commercial and non-commercial interests and includes European bodies such as the Fundamental Rights Agency and the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN) among others.

The Forum allows the Commission to engage all stakeholders in AI governance and gather technical expertise as well as operational feedback and advice on the implementation and enforcement of the AI Act.

- The Scientific Panel of Independent Experts[15]

Finally, the Scientific Panel of Independent Experts is a technical body established to support enforcement activities under the AI Act.

It assists the AI Office by handling qualified alerts signalling potential systemic risks arising from GPAI models and systems, and by providing tools, methodologies, and advice to assess and classify such models and systems, including those presenting systemic risks. It also supports the Commission, the AI Office, and national MSAs in their enforcement activities, upon request. As such, it guarantees equal access to expertise for all MSs.

The Panel is composed of up to 60 experts selected by the Commission for a renewable two-year term on the basis of their scientific or technical expertise in the field of AI, their independence from providers of AI systems or GPAI models, and their impartiality and objectivity. At least one, and no more than three, nationals from each MS and from each member of the European Free Trade Association participating in the European Economic Area – namely Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein – may be appointed to the Panel. Nationals of third countries may also be appointed as experts but should not represent more than one-fifths of the experts on the Scientific Panel.

The main distinction between the Scientific Panel and the Advisory Forum lies in the Panel’s independence, impartiality, and objectivity, as well as in its active contribution to the enforcement of the AI Act through its direct support to the AI Office and the national MSAs in fulfilling their enforcement tasks.

By creating these bodies, the EU has built a pool of experts that both supports the Commission in its supervisory and regulatory functions and ensures continuous feedback from stakeholders. This structure helps the EU maintain up-to-date expertise, identify implementation challenges, and strengthen the overall effectiveness of the European regulation of AI. However, this governance system brings together a wide range of actors operating across different forums, which may complicate coordination efforts.

Beyond the EU-level governance layer, the AI Act requires the creation of a governance architecture at a national level, to be established by each MS. They have a “significant degree of autonomy”[16] when it comes to forming their national governance architectures, particularly when it comes to designating the NCAs.[17]

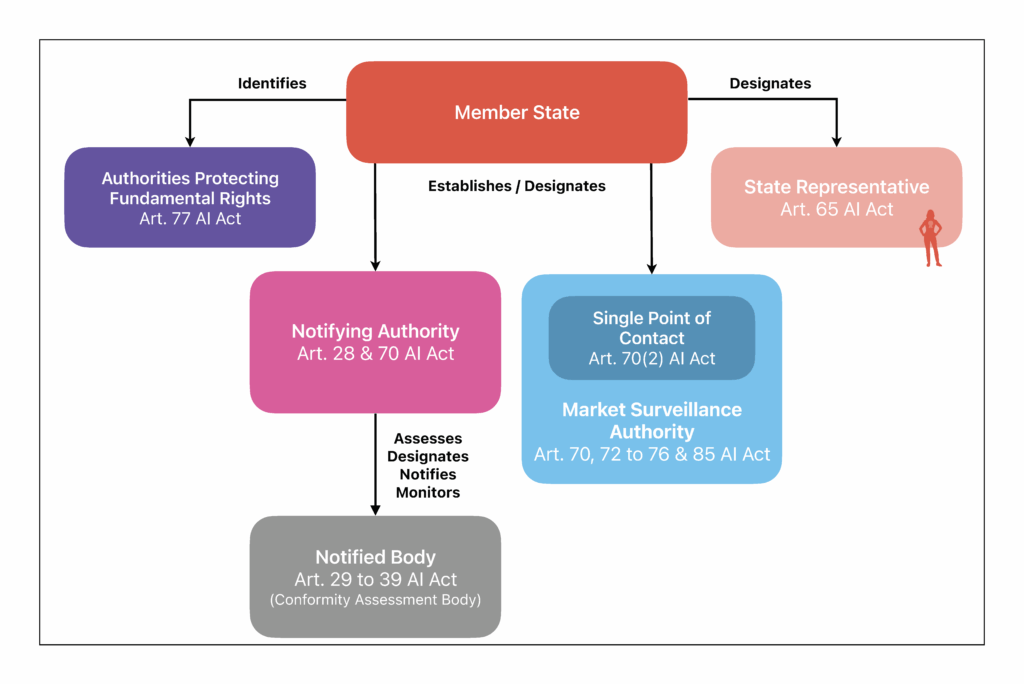

2.2 National architecture drawn up by member states.

The AI Act gives MSs a key role in the governance of AI, making them responsible for defining the national institutional architecture necessary for its implementation.[18]

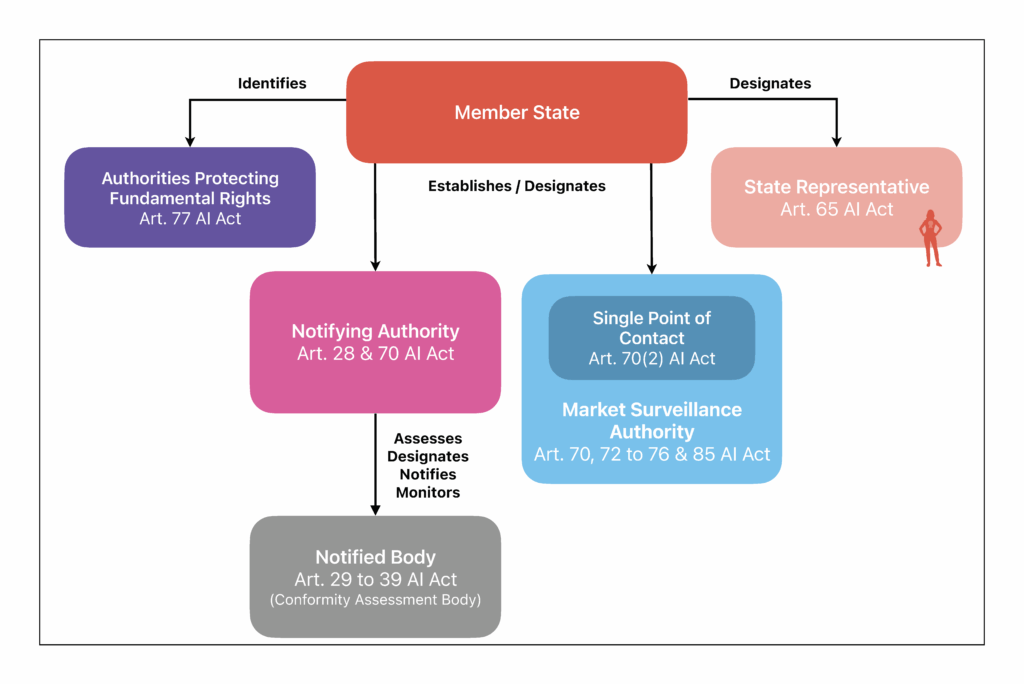

The legislation provides for the designation of several authorities that constitute the national governance architecture: notifying authorities, notified bodies, market surveillance authorities, single points of contact, authorities protecting fundamental rights, and state representatives.

According to recital 153 of the AI Act, the way states designate their NCAs is left at their discretion based on their “organisational characteristics and needs“, although they must comply with certain requirements.

Chart 2 – AI governance architecture at national level.

- Notifying authorities (NAs)[19]

Notifying authorities are independent and impartial public entities responsible for organising and overseeing the conformity assessment ecosystem.

To that end, they set up and carry out the procedures for the assessment, designation, notification, and monitoring of conformity assessment bodies. They may be supported by national accreditation bodies, which can be entrusted with assessment and monitoring tasks. NAs are also authorised to provide guidance and advice – to start-ups and SMEs – on the implementation of the AI Act.

MSs were required to designate or establish at least one NA – without limitation on their number – by 2 August 2025. These NAs must be organised in a way that guarantees objectivity and must be provided with sufficient technical, financial and human resources and infrastructure. They are required to comply with the confidentiality obligations set out in the AI Act and to ensure an appropriate level of cybersecurity. Their identity, contact details, and responsibilities must be communicated by MSs to the Commission.

- Notified bodies[20]

Notified bodies are independent conformity assessment bodies — formally notified by a NA — responsible for carrying out conformity assessment activities on high-risk AI systems to certify that they comply with the requirements of the AI Act before being placed on the market or put into service.

To be notified, a conformity assessment body must submit an application for notification to the NA of the MS in which it is established and comply with a set of requirements, including independence, impartiality, objectivity, confidentiality, adequate insurance coverage, sufficient resources, integrity in performing evaluations, and the necessary technical competence to ensure the reliability and performance of their results and activities. They may subcontract specific tasks, provided that the same requirements apply to the subcontractors and that the NA is duly informed.

Conformity assessment bodies established in third countries with which the EU has concluded an agreement may also be authorised to carry out the activities of notified bodies under the AI Act, provided that they meet the same requirements or equivalent level of compliance as those imposed on notified bodies established within the EU.

- Market surveillance authorities (MSAs)[21]

Market surveillance authorities are impartial public entities responsible for overseeing AI systems that are placed on the market, put into service, or made available within their territory. They ensure that high-risk AI systems remain in compliance with the requirements of the AI Act and applicable EU law throughout their lifecycle after being placed on the market. They enforce the AI Act by investigating cases of non-compliance and handling complaints and incident reports.

MSs were required to designate or establish at least one MSA – without limitation on their number – by 2 August 2025. These MSAs must also be organised in a way that guarantees objectivity and must be provided by MSs with sufficient technical, financial and human resources and infrastructure. They are required to comply with the confidentiality obligations set out in the AI Act and to ensure an appropriate level of cybersecurity. Their identity, contact details, and responsibilities must be communicated by MSs to the Commission.

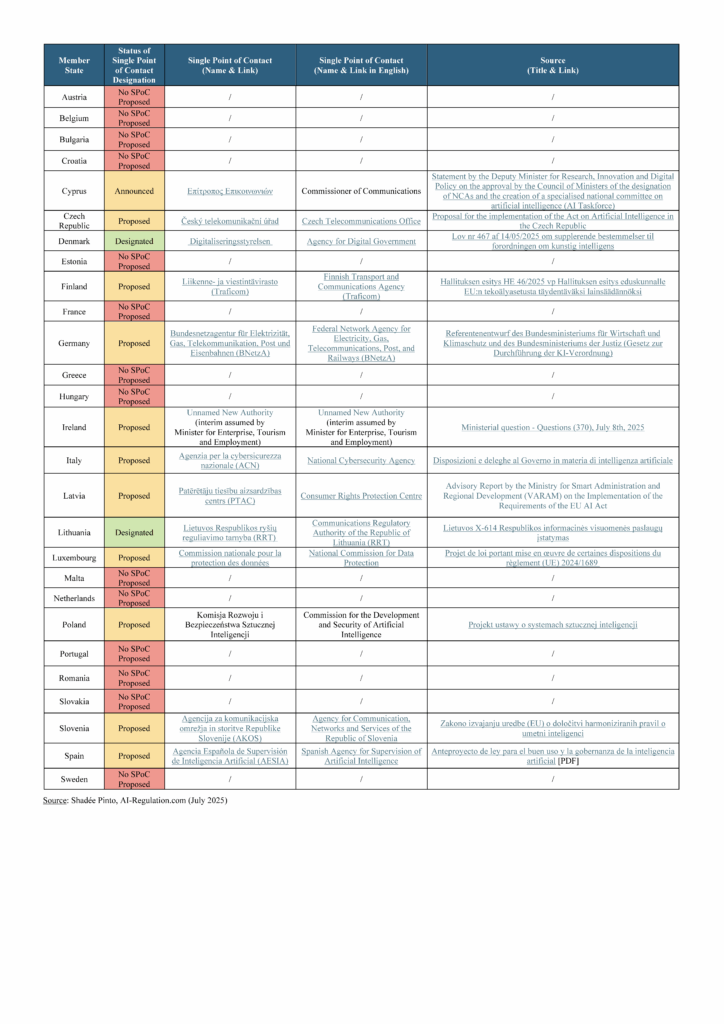

- Single points of contact (SPoCs)[22]

A single point of contact is a MSA designated to act as the main contact point in relation to the public and its counterparts at both national and EU levels. MSs are required to designate one MSA to act as SPoC, particularly when several MSAs are designated.

The SPoCs are briefly mentioned in the AI Act, but their missions are not explicitly defined.[23] Their designation aims to improve efficiency and coordination among national authorities and with their counterparts in other MSs.

- Authorities protecting fundamental rights[24]

Authorities protecting fundamental rights are national public authorities or bodies – such as data protection authorities or equality bodies -responsible for supervising and enforcing EU laws protecting fundamental rights in relation to the use of high-risk AI systems listed in Annex III of the AI Act.

To ensure that such systems do not infringe fundamental rights, these authorities may request access to documentation produced under the AI Actand request the MSAs to conduct tests to detect potential infringements.

The AI Act does not require the establishment of new authorities protecting fundamental rights. Rather, it provides that the authorities identified by MSs to supervise and enforce EU laws protecting fundamental rights in the context of high-risk AI systems will receive additional competences to fulfil these tasks. MSs were required to identify these authorities, make the corresponding list publicly available, and notify both the Commission and the other MSs by 2 November 2024.

- State Representatives[25]

State representatives are officials from public entities appointed by their MS for a renewable three-year term to sit on the AI Board. Each MS must designate a single representative, who acts as the main point of contact with the Board and with other MSs.

These representatives are responsible for facilitating coordination between the NCAs within their territory and for contributing to the tasks of the AI Board.

Since this article focuses on the obligation of MSs to designate their NAs, MSAs, and SPoCs pursuant to Article 70 of the AI Act, the other entities have been deliberately excluded from the analysis. For the sake of clarity and consistency, this article uses the term National Competent Authority (NCA) to refer to MSAs, SPoCs, and NAs.[26]

To ensure the successful implementation and enforcement of the AI Act, it is essential that MSs establish clear, identifiable and “well-coordinated”[27] national governance architectures. In order to understand how emerging national governance architectures are being formed, an overview of the state of designations has been formulated and then analysed to understand the trends.[28]

3. NATIONAL ARCHITECTURES UNDER CONSTRUCTION AROUND PRE-IDENTIFIED AND MULTIPLE AUTHORITIES.

The study of the AI governance architectures at national level reveals two dynamics: on the one hand, MSs had delayed designating their NCAs (3.1) and, on the other, the emergence of a still embryonic governance architectures, based on pre-identified, multiple authorities (3.2).

3.1 Delay in the announcement and legal enshrinement of the designation of NCAs.

This section addresses MSs’ compliance with the deadline set by the AI Act for designating their NCAs. To this end, it considers MSs where the designation of NCAs had not been made public and remained unknown (3.1.1). It then reviews the adoption of national implementation laws that formally established such designations by assessing the current status of their legal enshrinement (3.1.2).

3.1.1 Delay in the announcement of NCAs.

Although MSs were called upon to designate their NCAs by 2 August 2025, as per Article 70 of the AI Act, many had not yet officially designated or created them, and some had not even announced them. In fact, one week prior to the deadline, 13 states had not publicly announced their NCAs: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Estonia, France, Greece, Hungary[29], Malta[30], the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania[31], Slovakia, and Sweden.

These delays can generally be explained by three factors. Firstly, they resulted from difficulties in arbitrating the distribution of powers between administrative bodies. For instance, in France the designation process dragged on for months, reportedly due to difficulties in arbitrating the allocation of competences between various authorities.[32]

Secondly, they resulted from delays in the legislative process that have prevented states from officially creating their authorities or assigning new powers to designate authorities within the allotted timeframe. For example, Luxembourg had already submitted its implementation law to its parliament, months prior to the deadline. [33] However, official and final endorsement was delayed, as the legislature was still reviewing the text as of 2 August 2025.

Thirdly, they resulted from the political situation and dynamics in each MS. In Germany, for instance, early parliamentary elections were held in March 2025, leading to a period of political instability and a slowdown in the handling of certain matters, as governments often restrict themselves to day-to-day affairs during such times.

In practice, such NCA designations, along with the creation of new administrative entities and the allocation of new competences, are generally established by means of laws that adapt national law to EU law, or by other types of legal act depending on the legal characteristics of each state.[34] For the sake of clarity and consistency, these acts will be referred to as national implementation laws.

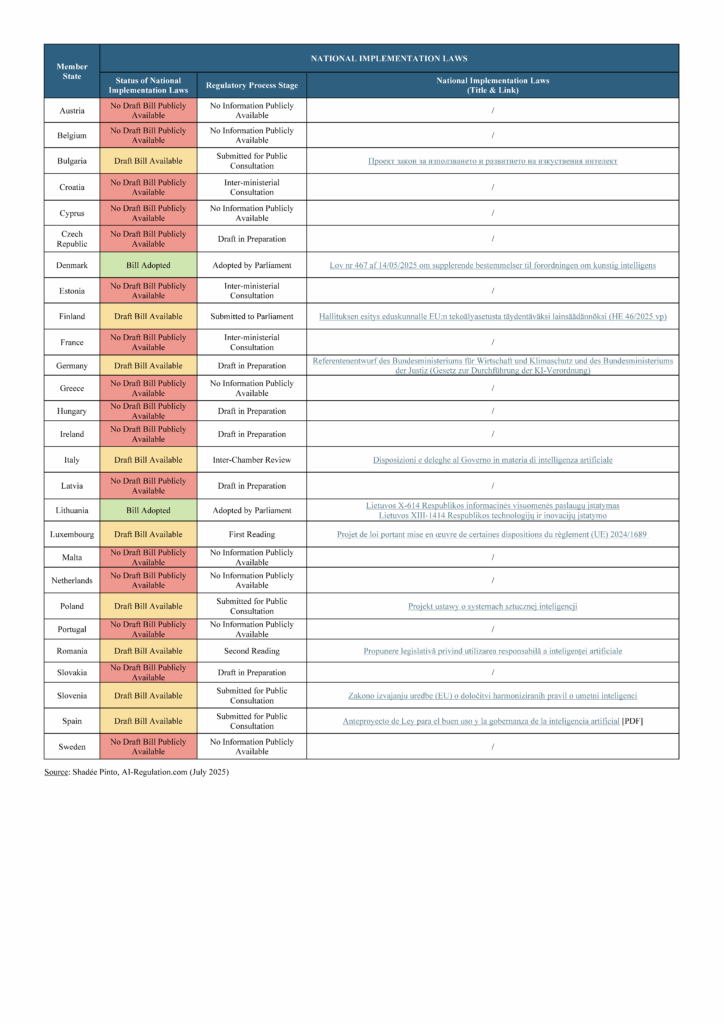

3.1.2 Delay in the legal enshrinement of the designation of NCAs.

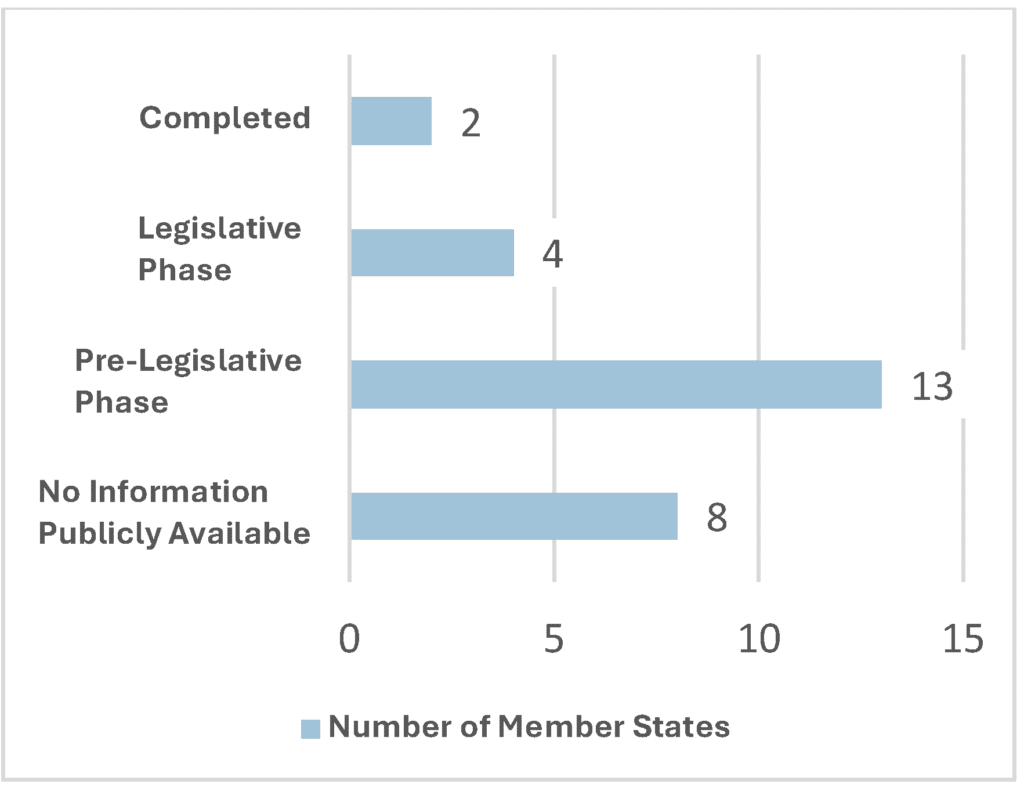

Regarding the legal enshrinement of NCA designations, MSs were not all at the same stage. A week prior to the deadline, 21 states had still not submitted a national implementation law to their respective parliaments, in order to legally enshrine the designation of their NCAs.

More precisely, 13 states were reported to be drafting a law or to have drafted one that had not yet been submitted to parliament.[35] As for the remaining 8 states, no bills or information on draft legislation were found.[36] However, with respect to the latter, it is possible that interministerial negotiations were underway but had not been announced, or that arbitration decisions had already been adopted but not made public. For example, although no implementation law had been made public, Cyprus had already announced its national competent authorities and was one of the first MSs to notify the Commission.

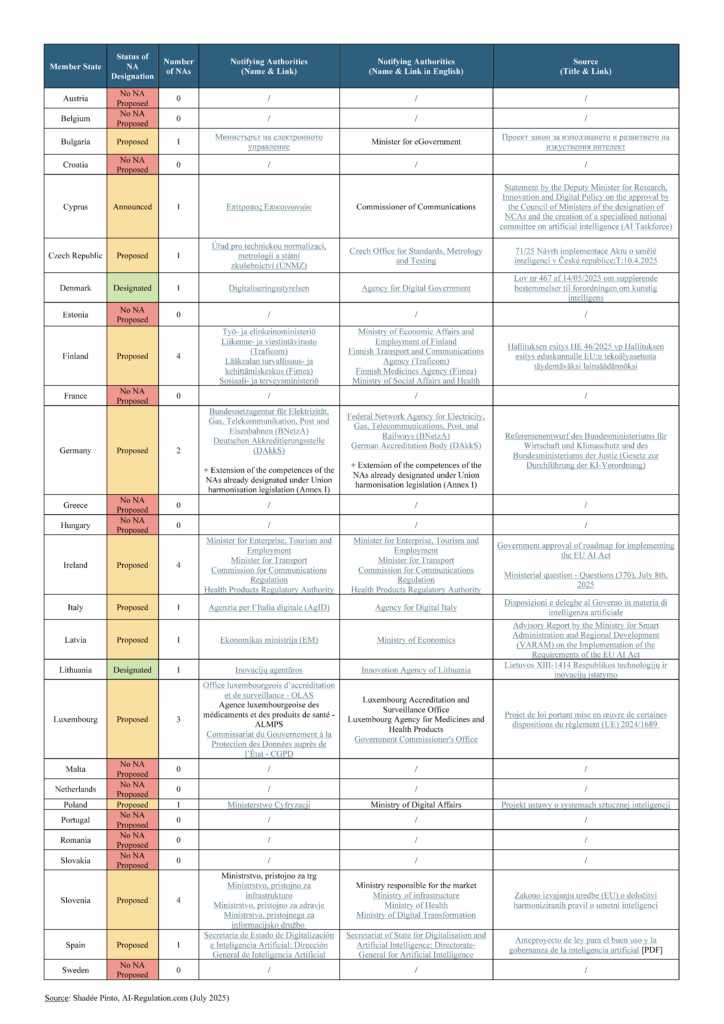

Table 1 – Status of the adoption of national implementation laws.[37]

This delay in establishing national AI governance architectures is not an unusual occurrence. For instance, the identification of authorities protecting fundamental rights under Article 77 of the AI Act was also delayed in some MSs.[38] On 2 August 2025, Italy had still not identified its authorities responsible for protecting fundamental rights, ten months after the date set by the AI Act.[39]

Nevertheless, this delay is likely to give rise to complications in the implementation of the AI Act. It delays identification of the authorities by European bodies, their counterparts in other MSs, and operators. It may suspend the internal organisation of the authorities, for which a reorganisation of priorities, objectives and teams, and possibly recruitment, may be necessary, as Article 70(3) of the AI Act requires that “national competent authorities are provided with adequate technical, financial and human resources, and with infrastructure to fulfil their tasks effectively under this Regulation”. In legal terms, this means that states were not in compliance with the AI Act, thereby exposing them to the riskof an infringement procedure in the most serious cases.[40]

This delay has been criticised by digital rights groups, which have called on the Commission to “press Member States to pass implementing laws and designate and sufficiently resource national competent authorities” and on MSs to “ensure that national AI governance structures are well-resourced and officially designated”.[41]

Finally, the majority of MSs (21) had not yet adopted – and in some cases even initiated – a procedure that officially assigns the powers devolved to the authorities under the AI Act.[42] Nevertheless, plans for 14 governance frameworks had been announced, giving a glimpse of the way AI governance could take shape within the EU.

3.2 National architectures based on multiple but pre-identified authorities.

A week prior to the deadline, it was possible to identify the governance architectures of the following 14 MSs based on publicly available information: Bulgaria[43], Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany[44], Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Slovenia and Spain.

A closer look at these national governance architectures reveals a significant disparity between the number of MSAs and NAs designated, with states tending to designate fewer NAs than MSAs (3.2.1). While some data protection authorities are granted competences under the AI Act -primarily as MSAs – others are entirely excluded (3.2.2). Finally, MSs tend to rely on pre-existing authorities rather than creating new ones (3.2.3).

3.2.1 Number of NCAs designated.

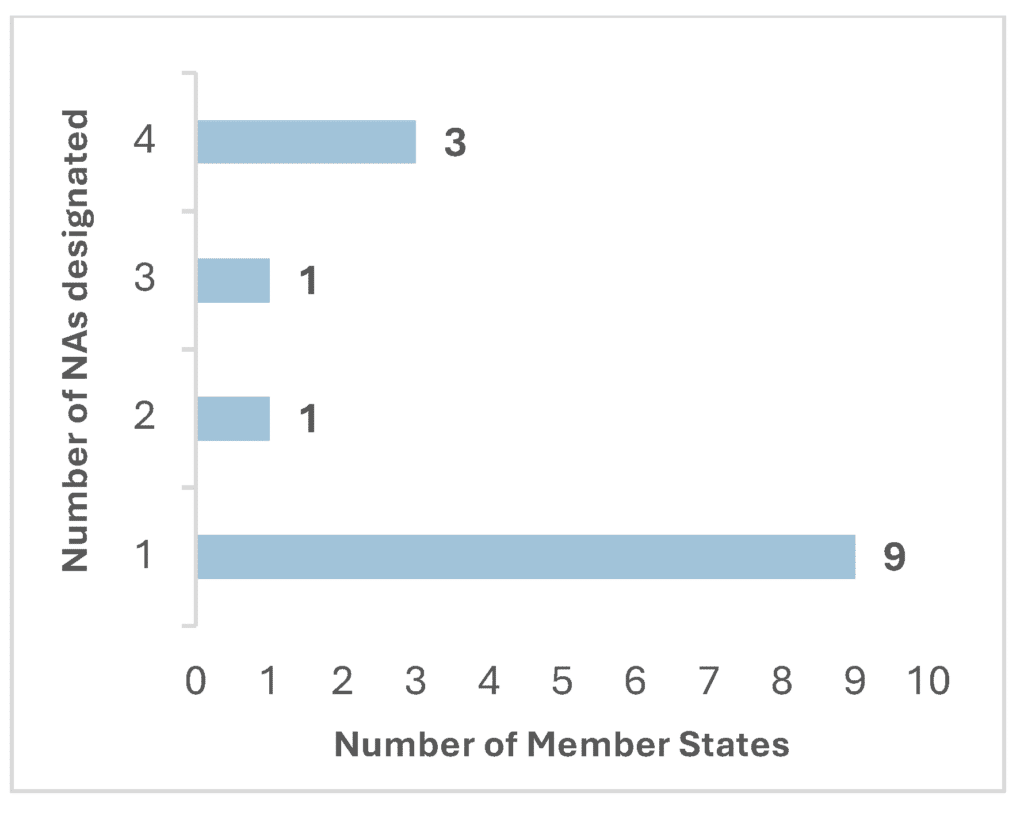

The majority of MSs limited themselves to designating a single NA, whereas a few chose to designate more: Germany (2), Luxembourg (3), Finland, Ireland, and Slovenia (4 each).[45]

Table 2 – Number of notifying authorities designated by Member States.[46]

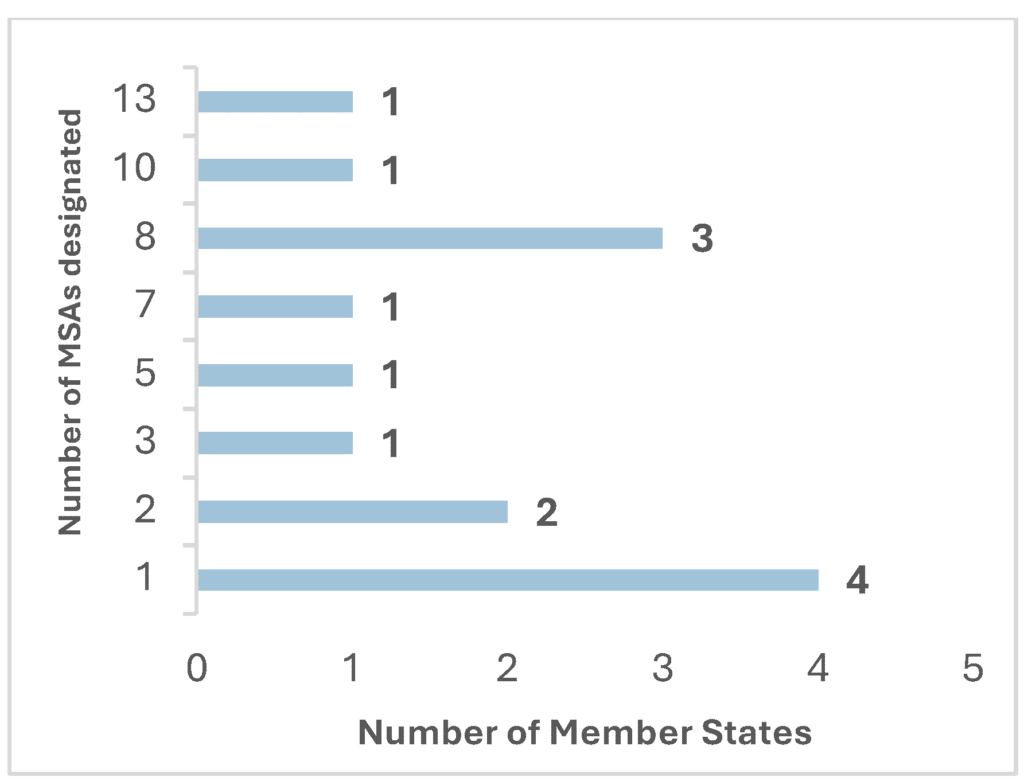

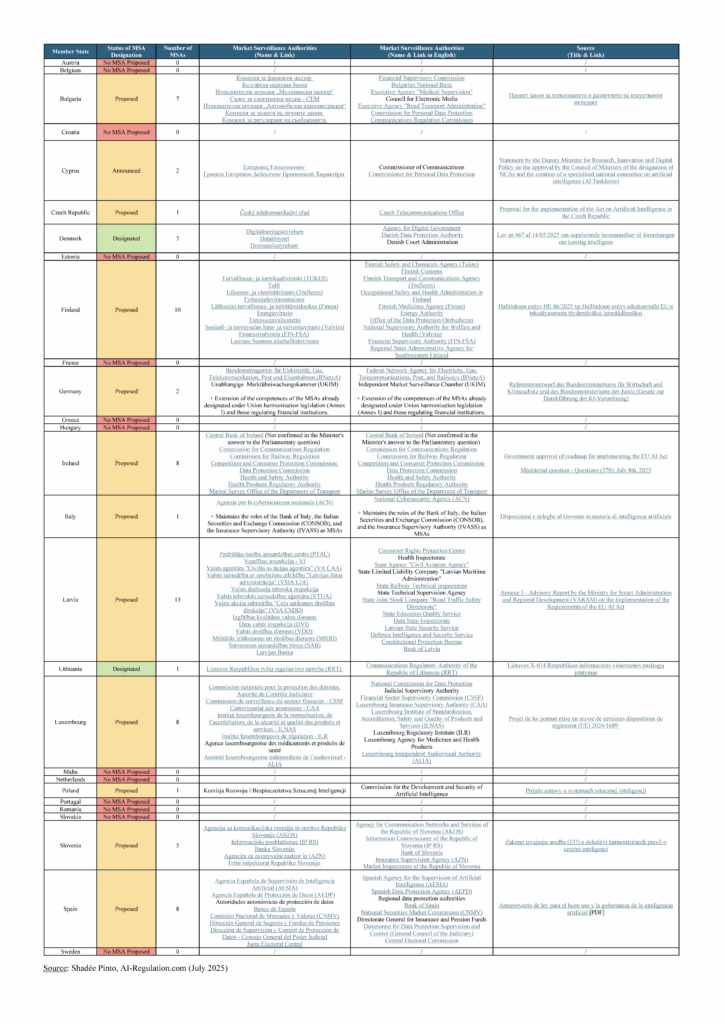

Conversely, MSAs tended to be more heterogeneous and greater in number, with their designation varying from 1 to 13 authorities per state. At the same time, a disparity emerged between MSs choosing to establish a limited number of MSAs – three or fewer authorities – and those that designated more than three.

Table 3 – Number of market surveillance authorities designated by Member States.[47]

This disparity reflects the diversity of national approaches to market surveillance.

On the one hand, employing a limited number of MSAs reflects a preference for centralised or even unified oversight of AI systems. On the other hand, relying on a higher number of MSAs reflects a more fragmented approach, which may be justified by the pursuit of sectoral specialisation. Both approaches are driven by different local institutional, economic, and administrative considerations.

Nevertheless, they both require sufficient financial, human, and technical resources[48] and structures in order to comply with Article 70 of the AI Act and ensure effective and efficient monitoring and oversight of AI systems. As Claudio Novelli et al. stated, “a lack of sufficient resources at MSAs can significantly slow the regulatory oversight of emerging AI technologies”.[49] As a matter of fact, lagging MSs that have not yet designated and properly resourced their MSAs could temporarily hinder their competitiveness, given the fact that speed to market is a crucial issue for businesses.

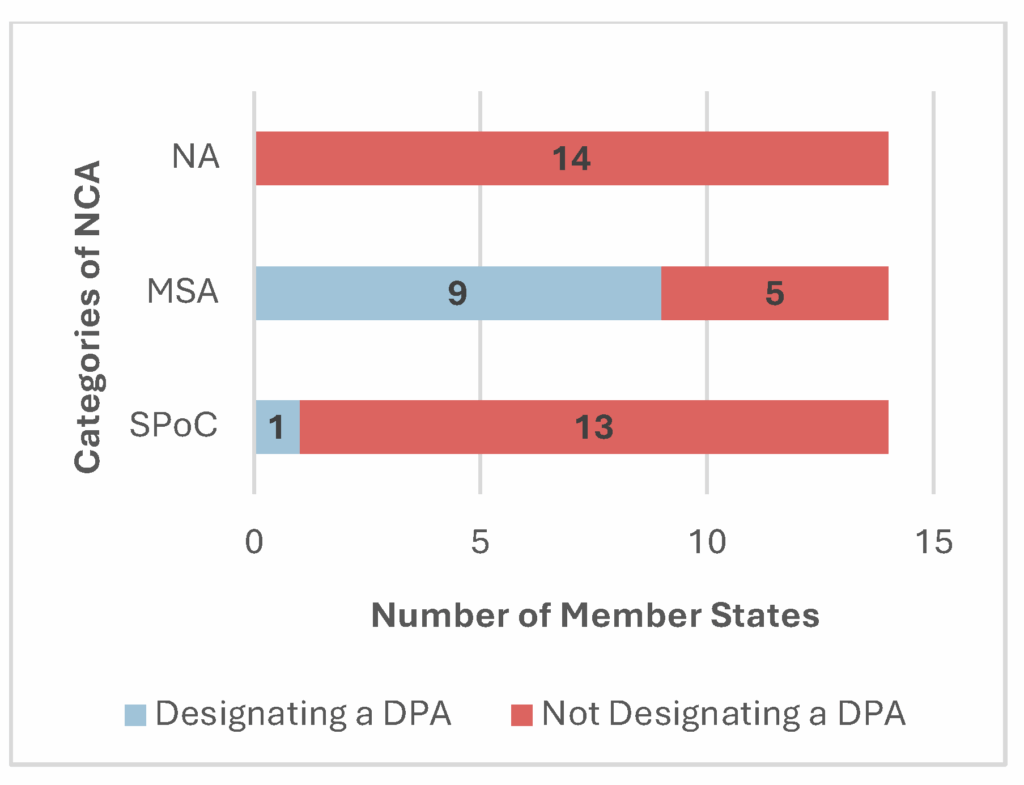

3.2.2 Designation of DPAs as NCAs.

The interconnection between personal data legislation and the AI Act raises the question of the role of data protection authorities (DPAs) in the regulation of AI, and the powers they may be afforded under the AI Act give pause for thought.[50]

In July 2024, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) published a statement on the role of DPAs under the AI Act.[51] In its statement, the EDPB recommends that MSs designate their national DPAs as their MSAs for high-risk AI systems, and as their SPoCs. The EDPB grounds its justification in the independence of the DPAs, their expertise and experience with related matters, and the legal and technical skills they possess.[52] Their position as a key player in the digital governance ecosystem would facilitate interactions among data protection and AI governance stakeholders, and enable a “unified, consistent and effective” approach across the relevant sectors.

Its position has been echoed by some national DPAs, such as the French (CNIL) and Polish (UODO).

Upon examining the governance architectures, it appeared that the EDPB’s recommendation had been partially followed by MSs since 9 DPAs had been designated as MSAs and 1 as SPoC.[53]

However, 5 MSs – namely the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, and Poland – completely excluded their DPAs from their governance architectures.

Such exclusion contrasts with the AI Act itself acknowledging DPAs legitimacy to oversee AI systems. In fact, Article 74(8) provides that MSs shall designate as MSA “either the competent data protection supervisory authorities under Regulation (EU) 2016/679 or Directive (EU) 2016/680, or any other authority designated pursuant to the same conditions laid down in Articles 41 to 44 of Directive (EU) 2016/680” to oversee high-risk AI systems listed in points 1 – when used for law enforcement purposes, border management and justice and democracy – as well as points 6, 7, and 8 of Annex III of the AI Act.[54]

Table 4 – Designation of data protection authorities as national competent authorities.

Germany’s decision to sideline its DPA – in favour of its Federal Network Agency (Bundesnetzagentur, BNetzA) and a newly created body within it – has been confirmed in a recently published draft law. However, this choice has been strongly criticised in a statement issued by the national and federal German DPAs, which described it as a “massive weakening of fundamental rights”. This approach stands in contrast to France’s recent decision – set out in a complex governance scheme – to designate its DPA as an MSA with 15 areas of AI use cases.[55]

As MSs proceed with their designations, divergences have become increasingly evident regarding the allocation of responsibilities to DPAsfor the implementation and enforcement of the AI Act. The exclusion of DPAs raises broader questions about how MSs perceive the role of DPAs and points to a potential lack of trust in their involvement in AI governance. This concern was explicitly highlighted by the German DPAs in the previously cited statement, which observed that “one of the reasons given for the proposal is to remove supposed barriers to innovation, as ‘data protection authorities focus primarily on the protection of fundamental rights,’ as the draft states.”.

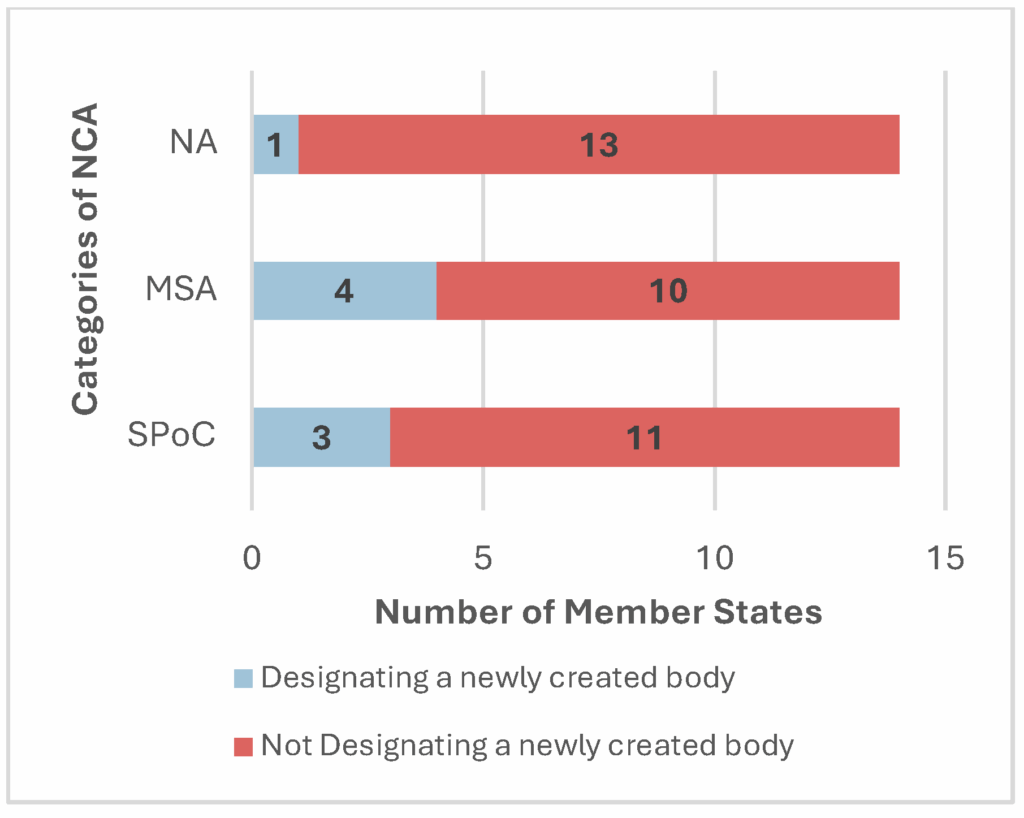

3.2.3 Designation of pre-existing authorities.

Finally, the lifespan of the designated authorities is a parameter that requires consideration, as it is likely to influence their ability to achieve their objectives quickly and effectively and to become fully operational as the provisions of the AI Act come into force. Authorities that have already been identified and invested with responsibilities under European legislation are likely to benefit from their prior experience, whereas newly created entities may experience delays due to internal organisation and integration into the digital regulation ecosystem. Nevertheless, new entities may enjoy a significant organisational advantage, as they can structure themselves specifically around the framework established by the AI Actand integrate the rapidly evolving nature of AI from the outset.

The majority of MSs had opted to designate pre-existing authorities, which already have responsibilities under other legislation, as NCAs.

However, 5 MSs – namely Germany, Luxembourg, Ireland[56], Poland and Spain – had entrusted the supervision of AI to newly created authorities or authorities that are acquiring their first responsibilities under the AI Act.[57] The latter two had chosen to create authorities that are specifically dedicated to AI, combining the functions of MSA and SPoC. In so doing, they made these new entities pivotal figures in the governance of AI at national level.

Table 5 – Number of Member States designating a newly created body as national competent authority.

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to identify and analyse the development of national AI governance architectures, focusing on the designation of NAs, MSAs and SPoCs. It also provided an opportunity to determine where MSs stand in relation to the AI Act timetable, which set the designation of these authorities for 2 August 2025.

The study revealed that one week prior to the deadline, 21 MSs had not yet submitted a national implementation law to their parliaments to legally enshrine their designations, while 13 had not announced the designation of their NCAs. Since the end of data compilation in July, some MSs have officially announced their NCAs (France, Ireland), published drafts of their national implementation laws (Germany, Hungary), or adopted their national implementation laws (Italy). Despite these developments, the majority of MSs still have not legally empowered their NCAs to fulfil their tasks.

The embryonic governance architectures highlight divergences in the number of designated NCAs. While MSs tend to rely on a limited number of NAs, approaches differ in market surveillance, where the number of designated authorities is considerably higher. Many of these authorities have already been identified by operators in the relevant sectors, as most of them already have powers under other legislation or are specifically identified for AI supervision.

Among these authorities are DPAs, whose potential contribution to AI governance seems to be questioned by several MSs. In fact, although some MSs have chosen to grant their DPA powers under the AI Act – mainly as MSAs – 5 MSs decided to exclude their DPAs from their national governance architectures. The German DPA, which appears to adopt a cautious and demanding stance regarding the risks AI models and systems may pose to fundamental rights, is one of the DPAs excluded from its MS’s national governance architecture. Conversely, the French DPA, which maintains an open dialogue and cooperative relationship with businesses, has recently been designated as an MSA and entrusted with the supervision of 15 areas of AI use cases.

As MSs announce their designations and organise their national governance, a complex and expansive bureaucracy is emerging, which runs counter to the EU’s efforts to simplify digital legislation – including the AI Act – carried out by the Commission under the forthcoming Digital Omnibus.[58] Despite this simplification process – initially called for by MSs and stakeholders – some MSs continue to increase institutional complexity by designating numerous NCAs. France serves as a notable example, opting for a complex fragmented governance structure with 17 different MSAs, often sharing mandates across 1 to 3 bodies (see page 11).[59]

This state-of-the-art overview, which focused on the situation prior to the entry into force of Article 70 of the AI Act, is intended to be updated to further assess progress in these designations and the shaping of the EU’s AI governance framework.

Appendix 1 – Table of key governance institutions under the AI Act.

Appendix 2 – Chart indicating AI governance architecture at EU level.

Appendix 3 – Chart indicating AI governance architecture at national level.

Appendix 4 – Table on the adoption of national implementation laws as of 23 July 2025.[60]

Appendix 5 – Table on the designation of notifying authorities as of 23 July 2025.[61]

Appendix 6 – Table on the designation of market surveillance authorities as of 23 of July 2025.[62]

Appendix 7 – Table on the designation of single point of contact as of 23 July 2025.[63]

To cite this article: Pinto, S. (2025). Who Oversees AI in the EU? The Designation of National Competent Authorities under the EU AI Act. AI-Regulation Papers 25-10-4. AI-Regulation.com.

These statements are attributable only to the author, and their publication here does not necessarily reflect the view of the other members of the AI-Regulation Chair or any partner organisations.

This work has been partially supported by MIAI @ Grenoble Alpes, (ANR-19-P3IA-0003) and by the Interdisciplinary Project on Privacy (IPoP) of the Cybersecurity PEPR (ANR 22-PECY-0002 IPOP).

[1] The term “National Competent Authorities” (NCAs) refers to both Notifying Authorities (NAs) and Market Surveillance Authorities (MSAs), as indicated in Article 3(48) of the AI Act. Since MSs are required, when they designate multiple MSAs, to appoint one of them to act as the Single Point of Contact (SPoC), the term NCA, in the context of this article, also includes SPoCs. For more information about each authority, see Appendix 1.

[2] Emborg, T. (2024, updated in May 2025). Overview of all AI Act National Implementation Plans. EU AI Act. Available at: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/national-implementation-plans/.

[3] Pók, L. (2024). Responsible authorities for the enforcement of the AI Act on national level. GDPR Blog. Available at: https://gdpr.blog.hu/2024/10/02/responsible_authorities_for_the_enforcement_of_the_ai_act_on_national_level.

[4] Parisini, E. and Dervishaj, E. (2025) Emerging models of national competent authorities under the EU AI Act. Conference on Digital Government Research. Vol. 26. Available at: https://proceedings.open.tudelft.nl/DGO2025/article/view/1007.

[5] The analysis excludes extensions of powers for authorities already designated under EU harmonisation legislation (Annex I of the AI Act) if those authorities are not explicitly named in the national implementation law or draft.

[6] The Hungarian government adopted Resolution no. 1301/2024, stating that an “Organisation” (Szervezet in Hungarian) should be appointed as the NA, MSA and SPoC, but it did not formally designate or establish any authority.

[7] The Malta Digital Innovation Authority (MDIA) and the Information and Data Protection Commissioner (IDPC) published information about their designations as NCAs on their respective websites. However, no formal designation has been made public yet.

[8] In Romania, a draft bill has been presented to Parliament. However, without substantial amendments, it may not be adopted, as the majority of the opinions gathered as part of the legislative procedure has been negative. One of the reasons given has been the failure to take account of the AI Act, and the lack of provision to adapt national law to the AI Act.

[9] A comprehensive table of each authority is provided in Appendix 1.

[10] Articles 3(47) and 64 of the AI Act, and Commission Decision C/2024/1459 of 24 January 2024 establishing the European Artificial Intelligence Office.

[11] General-purpose AI models are defined in Article 3 the AI Act as “ an AI model, including where such an AI model is trained with a large amount of data using self-supervision at scale, that displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications.”

The term should be distinguished from general-purpose AI systems which are “AI system which is based on a general-purpose AI model and which has the capability to serve a variety of purposes, both for direct use as well as for integration in other AI systems”.

[12] Articles 65 and 66 of the AI Act.

[13] Qualified alerts are issued by the Scientific Panel of Independent Experts to the AI Office when the Panel’s experts suspect that a GPAI model poses a concrete identifiable risk at EU level or that it can be classified as a GPAI model with systemic risk pursuant to Article 51 of the AI Act, in order to launch follow-up measures.

[14] Article 67 of the AI Act.

[15] Articles 68 and 69 of the AI Act, and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2025/454 of 7 March 2025 as regards the establishment of a scientific panel of independent experts in the field of artificial intelligence.

[16] Mazur, J. Novelli, C. and Choińska, Z. (2025). Should Data Protection Authorities Enforce the AI Act? Lessons from EU-wide Enforcement Data. SSRN. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5290513.

[17] Articles 70(1) and recital 153 of the AI Act.

[18] Article 70 of the AI Act.

[19] Articles 28 and 70 of the AI Act.

[20] Articles 29 to 39 of the AI Act.

[21] Articles 70, 72 to 76 and 85 of the AI Act, and Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 on market surveillance and compliance of products.

[22] Article 70 and recital 153 of the AI Act, and European Commission. (2025). Market surveillance Authorities under the AI Act Available at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/market-surveillance-authorities-under-ai-act#1720699867912-1.

[23] The AI Act only mentions single points of contact four times, twice in recital 153 and twice in Article 70 of the AI Act.

[24] Article 77 of the AI Act.

[25] Articles 65 and 66 of the AI Act.

[26] See footnote no.1

[27] Mazur, J. Novelli, C. and Choińska, Z. (2025). Should Data Protection Authorities Enforce the AI Act? Lessons from EU-wide Enforcement Data. SSRN. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5290513.

[28] For further details, see Appendices 4 to 7 and the interactive Excel table available at AI-Regulation.com.

[29] See footnote no.6.

[30] See footnote no.7.

[31] As mentioned in footnote no.8, Romania has drafted and submitted to its Parliament a law related to AI, however it does not address the designation of NCAs or any provisions to implement the AI Act.

[32] Contexte. (2025). Le mercato des autorités du règlement sur l’IA bute sur les processus démocratiques et les infrastructures critiques. Contexte. Available at: https://www.contexte.com/fr/actualite/tech/le-mercato-des-autorites-du-reglement-sur-lia-bute-sur-les-processus-democratiques-et-les-infrastructures-critiques_235039?go-back-to-briefitem=235039.

[33] Draft law 8476 implementing certain provisions of Regulation (EU) 2024/1689. Chambre des députés du Grand-duché du Luxembourg. Available at: https://www.chd.lu/fr/dossier/8476.

[34] As a reminder, in European law a regulation is a legal instrument of EU secondary legislation provided for under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). Its purpose is to ensure that European legislation is applied uniformly and simultaneously in all MSs. The regulation is binding in full, general in scope and direct in application, which means that it does not need to be transposed into national law or published in national official journals. However, the adoption of national legal acts may be necessary in order to organise the internal jurisdiction resources and to comply with new European regulations.

[35] States that are currently drafting a law or have a drafted a law but have not yet submitted it to parliament are Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain.

[36] States for which no information is available concerning whether they are drafting a law are Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal and Sweden.

[37] For further information, see Appendix 4.

[38] Kroet, C. (2025). Italy and Hungary fail to appoint fundamental rights bodies under AI Act. EuroNews. Available at: https://www.euronews.com/next/2025/05/06/italy-and-hungary-fail-to-appoint-fundamental-rights-bodies-under-ai-act.

[39] European Commission, Fundamental rights protection authorities with special powers under the AI Act. Available at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/fundamental-rights-protection-authorities-ai-act.

[40] The infringement procedure is a prerogative granted to the Commission enabling it to compel MSs to comply with EU law when they fail to do so or do not correctly apply EU legislation on the basis of Article 258 of the TFEU. This is a gradual procedure, ranging from a letter of formal notice to the defaulting state to referral to the Court of Justice of the EU.

[41] EDRi et al. (2025). Open letter “Keep AI Act National Implementation on Track”. EDRi. Available at: https://edri.org/our-work/open-letter-european-commission-member-states-keep-ai-act-national-implementation-on-track/.

[42] Denmark and Lithuania are the only states to have officially and legally designated their NCAs within the deadline set by the AI Act. Finland, Italy, Luxembourg and Romania had submitted their drafts to their respective parliaments, but these had not yet been officially adopted by the legislatures by 2 August 2025.

[43] As mentioned in section 1.2, Bulgarian architecture was put forward by a minor party in Bulgarian Parliament for public consultation but it has not been submitted to Parliament yet. It may therefore not represent the real intentions of the executive and legislative powers and may not be submitted to Parliament.

[44] As mentioned in section 1.2, as regards Germany, the document retrieved is not available on an official website and is more akin to a working or preparatory document, drafted before the 2025 German federal election.

[45] States that have designated a single NA are Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Spain.

[46] For further information, see Appendix 5.

[47] For further information, see Appendix 6.

[48] Novelli, C. et al. (2025). A Robust Governance for the AI Act: AI Office, AI Board, Scientific Panel, and National Authorities. European Journal of Risk Regulation. Cambridge University Press. 16(2). p.566-590. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-risk-regulation/article/robust-governance-for-the-ai-act-ai-office-ai-board-scientific-panel-and-national-authorities/98FEE97C8F9423DFCC28CBE063F9753B.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Mazur, J. Novelli, C. and Choińska, Z. (2025). Should Data Protection Authorities Enforce the AI Act? Lessons from EU-wide Enforcement Data. SSRN. Available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5290513.

[51] EDPB. (2024). EDPB adopts statement on DPAs role in AI Act framework, EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework FAQ and new European Data Protection Seal. EDPB. Available at: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/news/news/2024/edpb-adopts-statement-dpas-role-ai-act-framework-eu-us-data-privacy-framework-faq_en.

[52] The independence of the authorities is a requirement of Article 70 of the AI Act.

[53] Those MSs are Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Spain. Luxembourg went further, by being the only country to designate its DPA as a MSA and SPoC, thereby making it a cornerstone in the national governance of AI

[54] Regulation (EU) 2016/679, also known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), provides protection to individuals when their personal data are processed by private and public entities.

The Directive (EU) 2016/680 also known as Law Enforcement Directive (LED), provides protection to individuals when their personal data are processed by competent authorities for the purposes of the prevention, investigation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences or the execution of criminal penalties (judicial authorities, law enforcement authorities, etc.).

[55] The scheme is reproduced on page 11.

[56] The Irish Minister of State for Trade Promotion, Artificial Intelligence and Digital Transformation announced that a new central and coordination authority should be appointed and designated as the SPoC during a Ministerial question session. The interim responsibility will be assumed by the Minister of State for Trade Promotion, Artificial Intelligence, and Digital Transformation under the Ministry for Enterprise, Tourism and Employment.

[57] Luxembourg has designated the Luxembourg Agency for Medicines and Health Products (Agence luxembourgeoise des médicaments et produits de santé) as its NA and MSA. Its creation has been called for since 2019, but the draft bill submitted to Parliament in January 2025 had not yet been adopted.

[58] European Commission. (2025). Commission collects feedback to simplify rules on data, cybersecurity and artificial intelligence in the upcoming Digital Omnibus. Available at: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-collects-feedback-simplify-rules-data-cybersecurity-and-artificial-intelligence-upcoming.

[59] The Department for Enterprise (DGE) of the French Ministry of the Economy published a scheme outlining the MSAs responsible for monitoring high-risk AI systems. The scheme has been translated and reproduced on page 11.

[60] This appendix will be revised as further time pass.

[61] This appendix will be revised as further time pass.

[62] This appendix will be revised as further time pass.

[63] This appendix will be revised as further time pass.