The recent report of the OECD defining Artificial Intelligence (AI) incidents and related terminology closely followed a Corrigendum announcement by the European Parliament (EP) at the mid-April plenary session in Strasbourg, subsequent to the first reading of the forthcoming AI Act. The AI Act includes provisions for managing “serious incidents” involving AI systems. This article delineates the AI incident notification rules within the AI Act, illustrating a two-stage incident notification procedure. Key issues include the challenge of uniformly assessing the threshold for serious incidents, particularly for high-risk AI systems.

On May 6th, 2024, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a report that defines Artificial Intelligence (AI) incidents and their related terms. The report was published a few days after the announcement of a Corrigendum by the European Parliament (EP) at the mid-April plenary session in Strasbourg following the first reading of the forthcoming AI Act. Given that the AI Act also contains rules concerning what should occur in the event of a “serious incident”, this article explains the AI incident notification rules provided under the AI Act.

The AI Act’s incident notification procedure depicted in the flow chart is divided into two stages. Starting from the incident identification stage, questions arise as to how to uniformly assess the threshold at which an incident directly or indirectly involving a high-risk AI system is considered serious, since defining an incident as serious will depend on the reporting process being triggered. Therefore, the first section highlights the vagueness of the AI Act’s approach to identifying the seriousness of AI incidents when compared with the OECD Report, while the second section questions whether a uniform interpretation is possible across the Member States of the EU. The third and fourth sections present, respectively, the incident notification procedure laid down in Article 73 of the AI Act and its interplay with Union legislation.

1. Defining a Serious Incident; the AI Act Vs the OECD Report

The final text of the Corrigendum will be published in the EU Official Journal, following its formal endorsement by the Council. Nevertheless, the EP’s current Corrigendum document reflects the final shape of the EU AI Act, in which Article 3(49) defines a “serious incident” as:

| ‘an incident or malfunctioning of an AI system that directly or indirectly leads to any of the following:(a) the death of a person, or serious harm to a person’s health;(b) a serious and irreversible disruption of the management or operation of critical Infrastructure;(c) the infringement of obligations under Union law intended to protect fundamental rights;(d) serious harm to property or the environment;’ |

The wording “any” implies that there is no hierarchy of severity or requirement that there be cumulation in relation to the four specific incidents. Whenever one of these four incidents occur, a notification to the competent authorities will have to be made, no matter where the incident ranks in this list.

At first glance, the EU AI Act’s approach in terms of what should be considered a serious incident is in line with the OECD report approach, which clearly states that the ‘working definition of an AI incident is based [among others] (…) on the definition of a serious AI incident being proposed in the context of the EU AI Act’. However, it is possible to observe differences in some of the respective wordings.

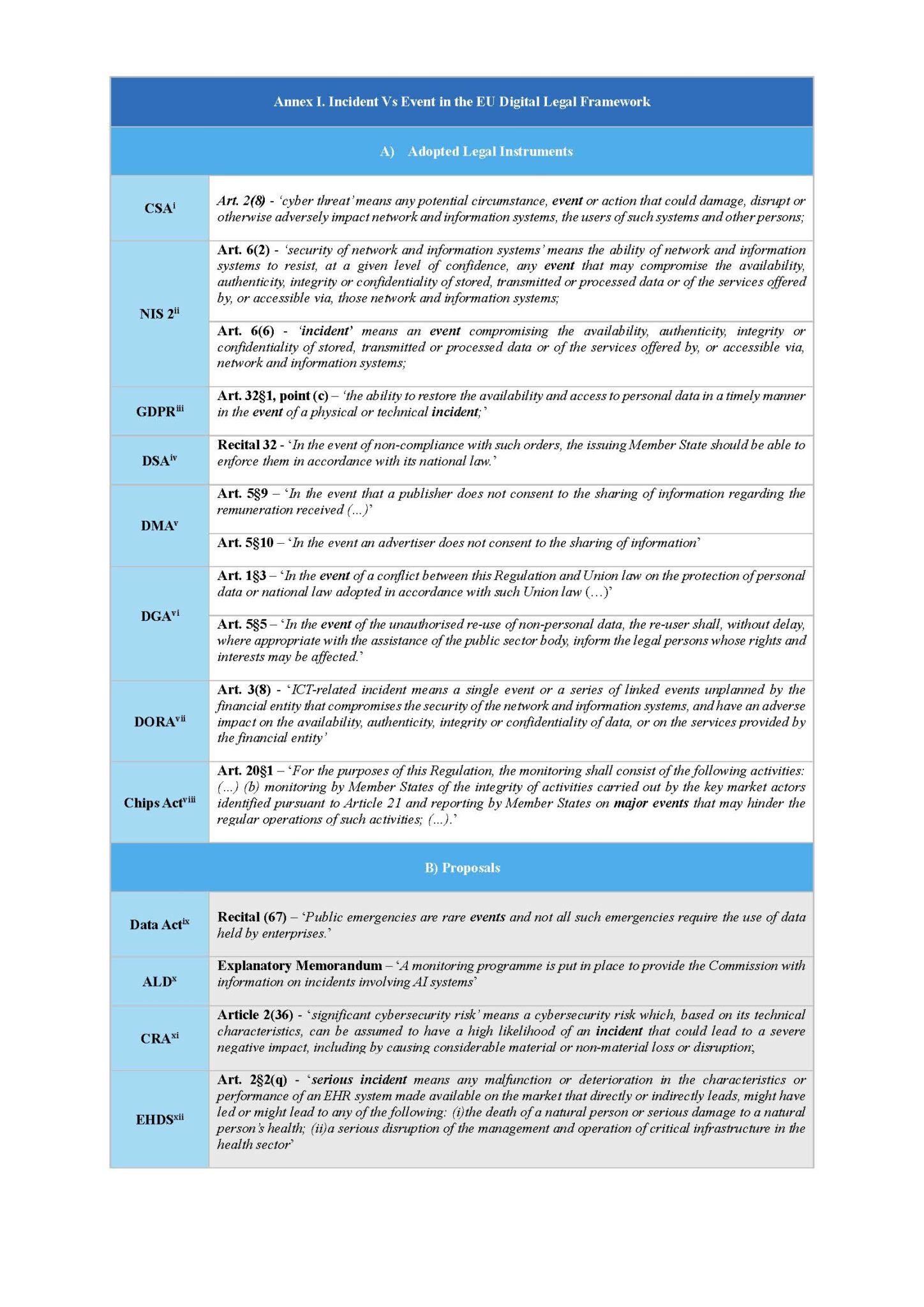

The first inconsistency is that the AI Act defines a serious incident as an ‘incident’, whereas the OECD report uses the term ‘event’ instead. Current and upcoming legal instruments in the EU Digital Policy are assessed in relation to the terms ‘event’ and ‘incident’ (Annex I). As one can observe, the term ‘event’ is often used in the EU digital regulatory framework to describe a situation that could potentially lead to an incident (e.g., damage or disruption in the case of the Cybersecurity Act, or a physical or technical incident in the case of the GDPR).

It should not be forgotten that the AI legislation was drafted using a risk-based approach. Considering that the possible occurrence of an incident is often included when describing the term “risk”, it seems that the European legislator opted to define a serious incident caused by AI as an outcome (a risk that has materialized) rather than a possible outcome (the usual meaning of the word risk), which is the guiding principle of the text. However, the inclusion of the category of General-Purpose AI (GPAI) models, which was the subject of great debate during the legislative process, entails systemic risks according to the AI Act, and reveals a contradiction in relation to whether an AI system or an AI model is involved.

| The systemic risks that GPAI models may pose ‘include, but are not limited to, any actual or reasonably foreseeable negative effects in relation to major accidents, disruptions of critical sectors and serious consequences to public health and safety’ (Recital 110 AI Act). |

It is possible to observe here that the systemic risks posed by some GPAI models may also lead to a ‘serious incident’, as is the case with AI systems. However, the scope has now been widened due to the use of plural terms. Hence, we are now not talking about the ‘serious harm to a person’s health’ or ‘a serious and irreversible disruption of the management or operation of [one] critical infrastructure’, but about ‘major accidents, disruptions of critical sectors and serious consequences to public health and safety’, which is more akin to what the OECD report calls an “AI disaster”, which is considered to be a category of serious AI incidents.

| OECD Report: An AI disaster is a serious AI incident that disrupts the functioning of a community or a society and that may test or exceed its capacity to cope, using its own resources. The effect of an AI disaster can be immediate and localised, or widespread and lasting for a long period of time. |

Article 55 of the AI Act on the “Obligations of providers of general-purpose AI models with systemic risk” adjudges that providers of such models should keep a ‘track of (…) relevant information about serious incidents (…)’. It seems therefore that the term “serious incident”, which could also be applied, when necessary, to the providers and deployers of high-risk AI systems, relates also to GPAI models with systemic risks. However, this approach contradicts the definition of the term in Article 3(49) and the meaning given under Recital 110 of the AI Act.

For example, Recital 110 states that a GPAI model with systemic risk could have ‘any actual or reasonably foreseeable negative effects’, while Article 3(49) does not refer to an eventual materialisation of a serious incident. However, this difference between the two interpretations is examined in the OECD report, which defines it as a “serious AI hazard”.

| OECD Report on “Serious AI Hazard”: A serious AI hazard is an event, circumstance or series of events where the development, use or malfunction of one or more AI systems could plausibly lead to a serious AI incident or AI disaster, i.e., any of the following harms:(a) the death of a person or serious harm to the health of a person or groups of people;(b) a serious and irreversible disruption of the management and operation of critical infrastructure;(c) a serious violation of human rights or a serious breach of obligations under the applicable law intended to protect fundamental, labour and intellectual property rights;(d) serious harm to property, communities or the environment;(e) the disruption of the functioning of a community or a society and which may test or exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources. |

Last but not least, it should be stressed that notification of AI-related incidents concerns only high-risk AI systems. According to the OECD report “Digital Economy Outlook 2024”, there has been a 53-fold increase in generative AI incidents and hazards globally since late 2022 according to reputable news outlets.

Source: OECD.AI (2024), AI Incidents Monitor (AIM), using data from the Event Registry.[1]

Large generative AI, which are “capable of generating text, images, and other content”, are considered under the AI Act to be General-Purpose AI (GPAI) models and therefore, fall under Chapter V of the AI Act, entitled “General Purpose AI Models”. Providers of such models are not obliged to follow the procedure described in Article 73. There is only one mention of GPAI models with systemic risks, as follows: “providers of general-purpose AI models with systemic risk shall (…) keep track of, document, and report, without undue delay, to the AI Office and, as appropriate, to national competent authorities, relevant information about serious incidents and possible corrective measures to address them; (…)”.[2]

2. Assessing the Seriousness of an Incident: Is Harmonisation Possible ?

The OECD states in its report that ‘assessing the seriousness of an AI incident is highly context-dependent’.

Building on its Österreichische (Austrian) Post judgment,[3] the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), in response to a request by the Varhoven administrativen sad (the Supreme Administrative Court of Bulgaria) for a preliminary ruling, indicated in a recent case[4]that, ‘the fear experienced by a data subject with regard to a possible misuse of his or her personal data by third parties as a result of an infringement of that regulation is capable, in itself, of constituting ‘non-material damage’ within the meaning of that provision’.[5] It was therefore required by the Varhoven administrativen sad to verify whether the fear can be regarded as well founded, in the specific circumstances experienced by the concerned individual. The fact that ‘each jurisdiction may define it differently’,[6] should be also taken into consideration in assessing the seriousness of an incident.

Another example, regarding the assessment of an incident’s seriousness in relation to the AI Act concerns whether critical infrastructures are involved. A serious and irreversible disruption of the management or operation of critical infrastructure is also considered a serious incident under the AI Act. The EU’s Critical Entities Resilience Directive (CER)[7], adopted in 2022, aims to strengthen the resilience of critical infrastructure in relation to a range of threats, including natural hazards, terrorist attacks, insider threats, or sabotage. Article 2(4) of the CER defines “critical infrastructures” as any asset, facility, equipment, network or system, or part of these infrastructures, which is necessary to provide a service that is ‘crucial for the maintenance of vital societal functions, economic activities, public health and safety, or the environment’[8] (an essential service). Therefore, any serious incident triggered (directly or indirectly) by an AI system that affects a critical entity’s infrastructure in the domain of energy, transport, health, drinking water, wastewater and space, requires that the competent authority be notified, according to the AI Act.

Critical entities are already required under the CER to notify the competent authority of incidents that significantly disrupt (or have the potential to disrupt) the provision of an essential service.[9] Therefore, the AI Act is not introducing a totally new reporting obligation. If an AI system is implicated in the disruption, the critical entity will also have to notify the designated national authority on AI of the incident.

As a result of making such a notification, however, the incident would have to be considered as significant and in order to do so, various factors would have to be taken into consideration, thereby entailing the risk that there is a differing implementation of the notifying obligation due to the divergent interpretations of the CER and the AI Act. Moreover, the CER obliges Member States to define the thresholds at which a disruption is considered as significant. This includes, among over criteria, the number of users of the service, the market share and the cross-border impact. and the impact of potential incidents but not only.[10] Risks posed by the non-harmonised assessment of the seriousness of an incident are, once again, at play.

The European AI Board, established under Article 65 of the AI Act, will be tasked with producing recommendations and written opinions as a result of evaluating and reviewing the AI Act, including reviewing, among others, the serious incident reports referred to in Article 73.[11] Moreover, the Commission must also ‘develop dedicated guidance to facilitate compliance with the obligations’ set out in Article 73§1 of the AI Act, within 12 months following the entry into force of the AI Act.[12] It is hoped therefore that further details will be provided by the Commission and the European AI Board over the months following the entry into force.

3. The Serious Incident Reporting Procedure under Article 73

The reporting obligation concerning serious incidents is provided under Article 73 of the AI Act. Providers of high-risk AI systems are placed on the “front line” of the reporting obligation’s scope. However, deployers of high-risk systems have not been excluded from the scope. Indeed, Article 26§5 provides that ‘where deployers have identified a serious incident, they shall also immediately inform first the provider, and then the importer or distributor and the relevant market surveillance authorities of that incident’.[13]

This implies that deployers will also have to include the occurrence of a serious incident in the operational monitoring of high-risk AI system. If the deployer is not able to reach the provider, the deployer will have to act as the “front line”, since in such cases Article 73 applies mutatis mutandis.

Moreover, the provider’s reporting of a serious incident to the national market surveillance authority takes place after the high-risk AI system is put on the market but also, when such an incident is identified during testing in real world conditions (outside the regulatory sandboxes).[14]

Article 73§2 of the AI Act also contains requirements concerning the maximum delays that are permitted following a serious incident to submit such a report (Table 1). Once the provider or, where applicable, the deployer, becomes aware of the serious incident, the report would have to be submitted immediately after a causal link is established between the AI system and the serious incident, and the report must not be sent any longer than 15 days after the incident has occurred. A delay of 15 days is required due to the fact that a serious incident may affect the capacity of the provider or the deployer to respond immediately.

The severity of the incident can therefore serve as a legitimate basis for the provider to justify a delay in relation to how quickly the incident is reported. So, we are again faced with the same scenario as the assessment of the seriousness of an incident.[15] How is ‘severity’ determined? When one takes into account the serious incident categories that have been already identified in the AI Act,[16] evaluating an incident’s severity will probably take place throughout the lifecycle of the incident. The number of people whose personal data has been exposed could eventually be used as an assessing criterion. However, the AI Act does not provide any thresholds or non-exhaustive list on this. This implies that it will be assessed on a case-by-case basis by the competent national authorities (market surveillance authority and public authorities or bodies that supervise or enforce the obligations under Union law). Such an assessment could be conducted differently across the EU.

The maximum delay of 15 days will be reduced to 2 days in the event of ‘a widespread infringement’ or of a serious and irreversible disruption of the management or operation of critical infrastructure. In the event of a person’s death, the provider or deployer of a high-risk AI system must report the incident immediately, or no later than 10 days, after determining or suspecting a link between the AI system and the death. Providers are given every chance of being compliant with their reporting obligation, as the AI Act offers them the option of submitting an incomplete initial report prior to delivering a report within the agreed time delay.

The serious incident reporting obligation is not entirely met as a result of submitting the report. The provider is still obliged to conduct ‘without delay, the necessary investigations in relation to the serious incident and the AI system concerned’, which include ‘a risk assessment of the incident, and corrective action’.[17] The provider should refrain from conducting ‘any investigation which involves altering the AI system concerned in a way which may affect any subsequent evaluation of the causes of the incident, prior to informing the competent authorities of such action’.[18] During the investigations, the provider must cooperate ‘with the competent authorities, and where relevant with the notified body concerned’ in order to comply with this obligation.

Upon receipt of the notification or no later than 7 seven days post-receipt, the relevant market surveillance authority must take all appropriate measures and inform the national public authorities or bodies which supervise or enforce the obligations under Union law, therefore protecting fundamental rights.[19]

These measures include a) the withdrawal or recall[20] of the high-risk AI system that presents a serious risk if there is no other effective means available to eliminate the serious risk or b) removing the system from the market.[21] The Commission is notified immediately about the measure taken through the Rapid Information Exchange System (RAPEX).[22] It is important to stress that the decision taken by the market surveillance authority to qualify a high-risk AI system as presenting a serious risk is based ‘on an appropriate risk assessment that takes account of the nature of the hazard and the likelihood of its occurrence’; ‘The feasibility of obtaining higher levels of safety and the availability of other products presenting a lesser degree of risk shall not constitute grounds for considering that a product presents a serious risk’.[23]

4. The Interplay with Union Legislation

According to Article 73, a decision needs to be made about whether a high-risk AI system, placed on the market or put into service by a provider, is catered for via Annex III or is a safety component of devices,[24] or is itself a device, which would be covered by Regulations (EU) 2017/745 and (EU) 2017/746.[25]

In the first case, if the high-risk AI system referred to in Annex III is subject to Union legislative instruments that lay down reporting obligations equivalent to those set out in the AI Act, the notification of serious incidents, established under Article 73 of the AI Act, would only involve those that lead to obligations under Union law, intended to protect fundamental rights, being infringed. The protection of fundamental rights is at the core of the AI Act; however, assessing whether there is a reporting “equivalence” is once again open to interpretation. Should the term “equivalence” be understood as equivalent in terms of procedure or seriousness?

Moreover, while the focus on the protection of fundamental rights may be understandable in some cases where the high-risk AI system falls within the scope of a Union law that is not per se related to such a right (e.g., the Critical Entities Resilience Directive), it creates confusion in other cases where the relevant Union law concerns a fundamental right, such as the protection of personal data under the GDPR.

Regarding the management and operation of critical digital infrastructure, Recital 55 refers for example to the infrastructures listed in point (8) of the Annex to the CER Directive (e.g., IXP,[26] DNS,[27] top-level-domain name registries, cloud computing services, data centre services, etc…). Under this Directive, critical entities are obligated to notify the competent authority without undue delay of any incidents that ‘significantly disrupt or have the potential to significantly disrupt the provision of essential services’.[28] The term “disruption” is understood under the CER Directive as the interruption of essential services by natural hazards, terrorist attacks, insider threats, or sabotage. It is possible to imagine that the materialisation of such threats may somewhat affect an AI system’s behavior indirectly and therefore, result in serious harm to a person’s health,[29] serious and irreversible disruption to the management or operation of critical infrastructure, or even serious harm to property or the environment. The requirement to notify the competent authority of an incident that leads to the infringement of obligations intended to protect fundamental rights under Union law, an obligation that has been in the AI Act since its inception, is therefore understandable.

However, data centres and cloud computing service providers are also considered to be data processors and therefore, are also subject to the provisions of the GDPR,[30] since ‘personal data which are, by their nature, particularly sensitive in relation to fundamental rights and freedoms merit specific protection as the context of their processing could create significant risks to the fundamental rights and freedom’[31] of natural persons. Therefore, such providers are required to notify the competent authority of any personal data breach that could infringe the protection of natural persons’ data, which is a fundamental right under Article 8(1) of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU and Article 16(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU.[32]

The GDPR imposes similar notification requirements to the AI Act in relation to the entities that fall within its scope. The data controller must notify the national supervisory authority of a data breach within 72 hours, while the processor must ‘notify the controller without undue delay after becoming aware of a personal data breach’.[33]

If we consider that the GDPR provides an “equivalent” reporting obligation to that set out in Article 73 of the AI Act, this would logically mean that if a data controller becomes aware of a data breach, which is directly or indirectly caused by an AI system, it is likely to result in a risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons. The data controller would subsequently also have to notify the national market surveillance authority of such an incident under the AI Act, in addition to the national data protection authority. This is a situation that risks resulting in the entities that fall within the scope of two or more Union laws experiencing “notification overload”.[34]

This limiting of the notification of serious incidents to when obligations under Union law, intended to protect fundamental rights, are infringed, also applies to those high-risk AI systems that are safety components of devices, or are themselves devices, and as such are covered by the Medical Devices Regulation[35] (MDR) and the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Regulation[36] (IVDR).[37]Both regulations contain new rules regarding the reporting of serious incidents,[38] and both define serious incidents as those that ‘directly or indirectly led, might have led or might lead to (…) the death of a patient, user or other person; the temporary or permanent serious deterioration of a patient’s, user’s or other person’s state of health; or a serious public health threat’.[39] However, in this case, the notification will have to be made, ‘to the national competent authority chosen for that purpose by the Member States where the incident occurred’[40] and not to the market surveillance authority,[41] as provided under Article 73§1 of the AI Act.

These statements are attributable only to the author, and their publication here does not necessarily reflect the view of the other members of the AI-Regulation Chair or any partner organizations.

This work has been partially supported by MIAI @ Grenoble Alpes, (ANR-19-P3IA-0003) and by the Interdisciplinary Project on Privacy (IPoP) of the Cybersecurity PEPR (ANR 22-PECY-0002 IPOP).

[1] OECD.AI (2024), “AI Incidence Monitor (AIM)”, OECD.AI Policy Observatory (database).

[2] Article 55§1, point (c), AI Act

[3] Case C-300/21, Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) of 4 May 2023, UI v Österreichische Post AG, ECLI:EU:C:2023:370.

[4] Case C-340/21, Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) of 14 December 2023, VB v Natsionalna agentsia za prihodite, ECLI:EU:C:2023:986.

[5] Para. 86

[6] OECD Report

[7] Directive (EU) 2022/2557 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on the resilience of critical entities and repealing Council Directive 2008/114/EC, PE/51/2022/REV/1, OJ L 333, 27.12.2022, p. 164–198.

[8] Article 2(5) CER

[9] Article 15 CER

[10] Establishing a harmonised approach across the EU on the thresholds above which an incident notification should be triggered, which is a typical issue in cybersecurity for those aware of the EU Directive NIS.

[11] Article 66 AI Act.

[12] Article 73§7 AI Act.

[13] If the deployer is a law enforcement authority, this reporting obligation will not include having to reveal any sensitive operational data to the competent authority.

[14] Article 60§7 AI Act

[15] See previous section.

[16] a) the death of a person, or serious harm to a person’s health; (b) a serious and irreversible disruption of the management or operation of critical Infrastructure; (c) the infringement of obligations under Union law intended to protect fundamental rights; (d) serious harm to property or the environment.

[17] Article 73§6 AI Act.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Article 73§7 AI Act.

[20] Article 3(23) of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 on market surveillance and compliance of products: ‘“withdrawal” means any measure aimed at preventing a product in the supply chain from being made available on the market’.

[21] Article 19§1 of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 on market surveillance and compliance of products.

[22] Article 73§11 AI Act and Article 20 of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 on market surveillance and compliance of products.

[23] Article 19§2 of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 on market surveillance and compliance of products.

[24] Article 73§9 AI Act.

[25] Article 73§10 AI Act.

[26] Internet exchange points

[27] Domain name services

[28] Article 15 CER

[29] Probably psychological health (e.g., fear)

[30] Article 1§9 CER: ‘This Directive is without prejudice to Union law on the protection of personal data, in particular Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council (28) and Directive 2002/58/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council’.

[31] Recital 51 GDPR

[32] Article 33 GDPR.

[33] Article 33§2 GDPR

[34] In my view, it would have been preferable to require national competent authorities, which are already obliged to receive notifications under other Union legislation, to refer any incident involving a high-risk AI system to the market surveillance authority, as they are likely to be the first to be informed.

[35] Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on medical devices, amending Directive 2001/83/EC, Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 and Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 and repealing Council Directives 90/385/EEC and 93/42/EEC, OJ L 117, 5.5.2017, p. 1–175.

[36] Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and repealing Directive 98/79/EC and Commission Decision 2010/227/EU, OJ L 117, 5.5.2017, p. 176–332.

[37] Article 73§10 AI Act.

[38] Article 87 MDR and Article 82 IVDR.

[39] Article 2(65) MDR and Article 2(68) IVDR.

[40] Article 73§10 AI Act.

[41] National authority carrying out activity and taking measures pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on market surveillance and compliance of products and amending Directive 2004/42/EC and Regulations (EC) No 765/2008 and (EU) No 305/2011, PE/45/2019/REV/1, OJ L 169, 25.6.2019, p. 1–44.