One year after “AI’s Sputnik moment,” the global regulatory response to DeepSeek has produced a starkly bifurcated outcome: constrained in the West, yet surging 960% worldwide. This comprehensive study documents the regulatory storm, unpacks the legal concerns, and confronts an uncomfortable truth about the limits of extraterritorial enforcement.

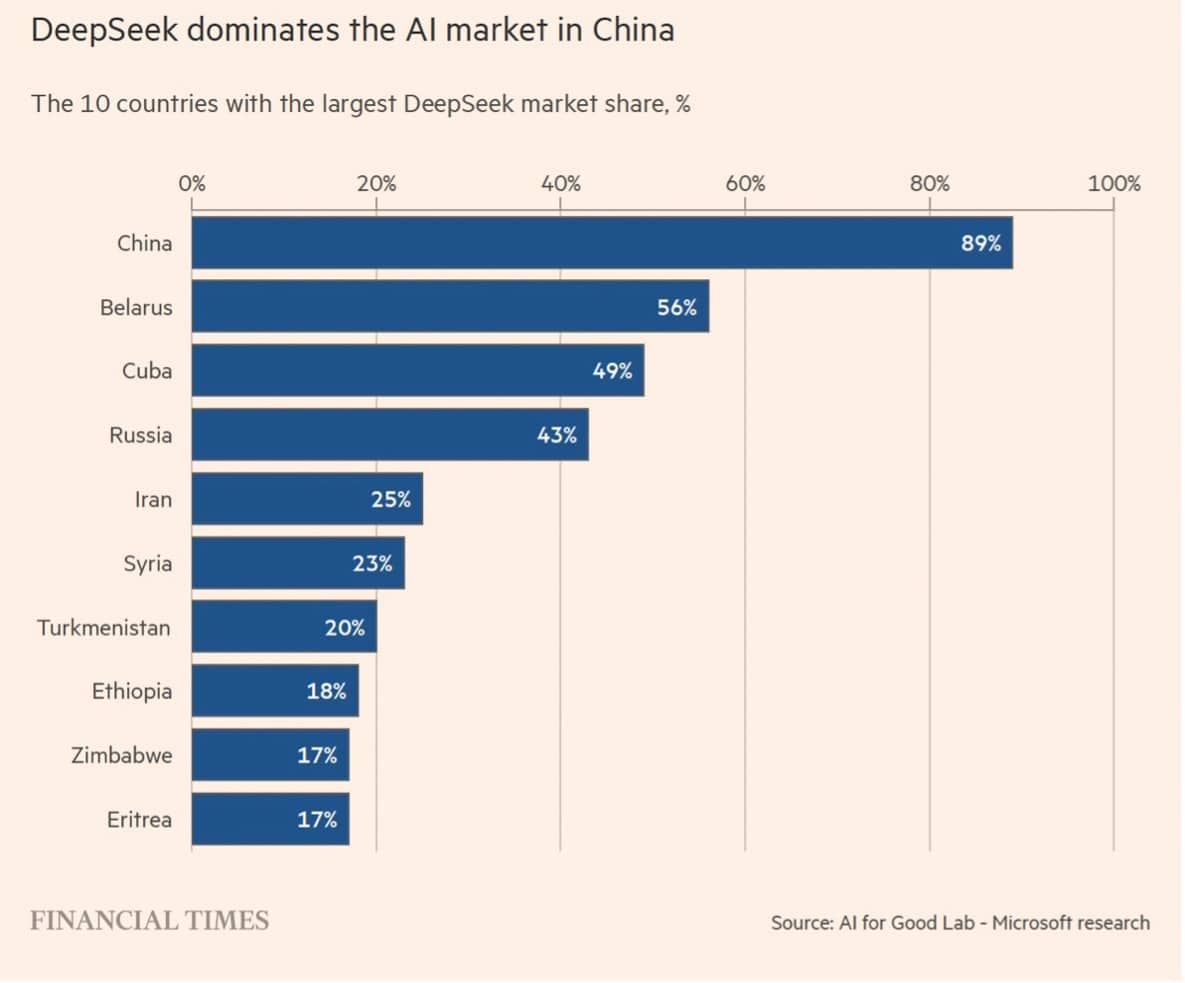

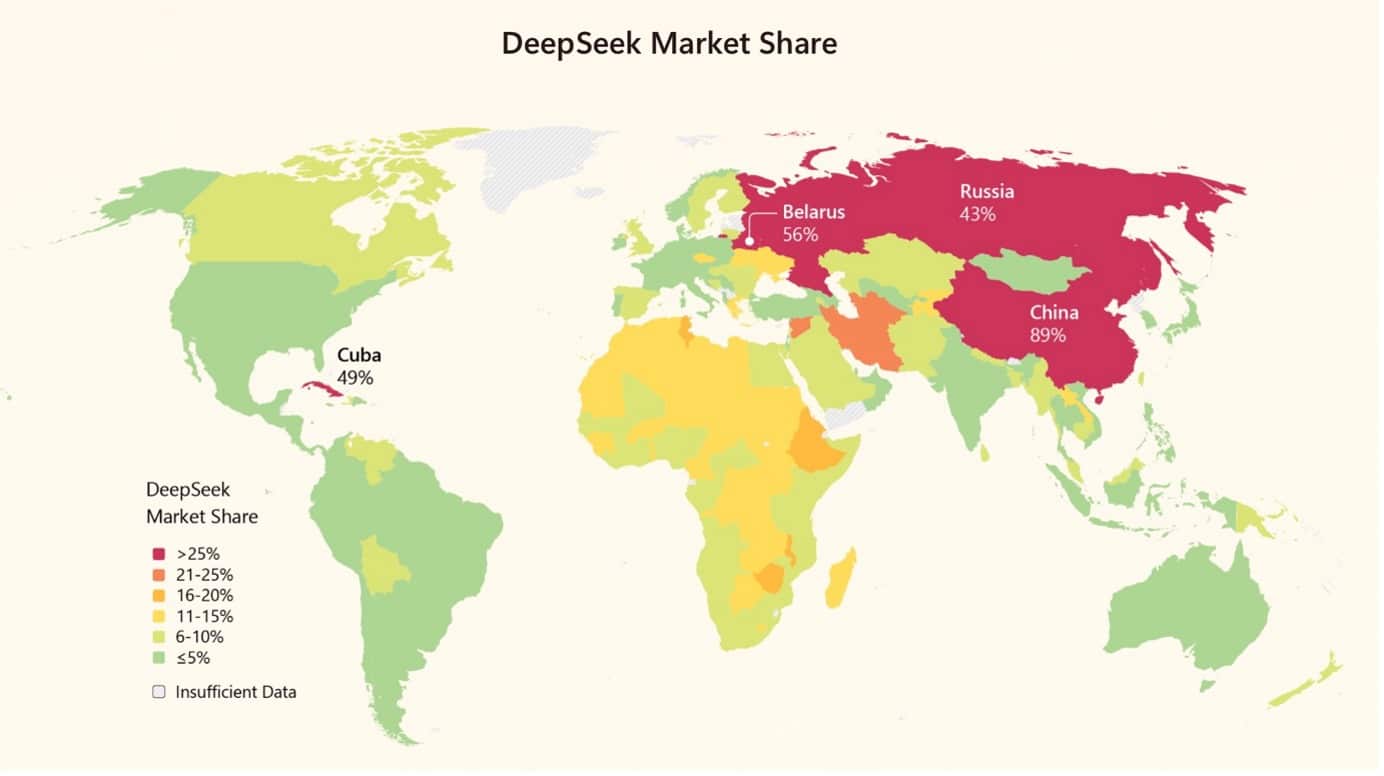

| On January 27, 2025, the Chinese artificial intelligence startup DeepSeek released its R1 reasoning model, an event venture capitalist Marc Andreessen termed AI’s Sputnik moment. The release precipitated immediate market turmoil, Nvidia lost $589 billion in market value in a single trading session, and sparked an unprecedented wave of regulatory scrutiny spanning data protection authorities, national security agencies, cybersecurity regulators, and legislative bodies across multiple continents. One year later, this article provides a comprehensive assessment of the global regulatory reactions to DeepSeek, evaluating both the substance of regulatory concerns and the effectiveness of the interventions that followed. The article makes four principal contributions. It documents the cascade of regulatory responses across jurisdictions; unpacks the substantive legal concerns that animated regulatory action; examines the national security dimensions that distinguished DeepSeek from prior AI enforcement episodes; and offers an evaluative assessment addressing three fundamental questions: whether DeepSeek responded adequately to regulatory demands; what lessons can be drawn for regulators and AI developers; and whether regulatory interventions constituted an effective brake on DeepSeek’s global adoption. Part I maps the data protection authority responses across Europe and Asia. Italy’s Garante became the first Western authority to impose a ban (January 30, 2025), after DeepSeek’s initial response to information requests was deemed inadequate and the company asserted, unpersuasively, that EU law did not apply to its operations. Investigations followed rapidly in Ireland, Belgium, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Spain, Portugal, Poland, Lithuania, Croatia, and Germany. The European Data Protection Board expanded its ChatGPT Task Force into a broader AI Enforcement Task Force to coordinate responses. South Korea’s Personal Information Protection Commission pursued a parallel but strikingly different trajectory: through sustained engagement, the PIPC achieved cooperative compliance and service resumption within ten weeks. Part II focuses on the substantive data protection concerns that animated regulatory action. Five recurring themes emerge: (1) transparency deficits and opaque processing policies failing to meet GDPR Articles 12–14 requirements; (2) cross-border data flows to China without adequate safeguards, raising questions under both Chapter V transfer rules and Article 32 security obligations; (3) the use of personal data for model training without clear legal bases or opt-out mechanisms; (4) inadequate safeguards for children’s data, including absent age verification at launch; and (5) the failure to designate an EU representative under Article 27 GDPR until late May 2025, almost five months after the Italian ban. The section includes critical analysis of whether certain DPA framings of the ‘transfer’ issue correctly apply GDPR Chapter V to direct-collection scenarios, suggesting that some regulatory communications may have conflated distinct legal frameworks. Part III examines regulatory responses beyond data protection, focusing on confidentiality, cybersecurity, and national security concerns. The United States executed a multi-layered prohibition strategy encompassing the Department of Defense, NASA, the Department of Energy, Congress, and multiple state governments, with bipartisan federal legislation introduced in February 2025. Similar government device bans proliferated across allied democracies including Australia, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Canada, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and the Czech Republic. The section analyzes the distinct rationale underlying national security responses, concerns about potential data access by Chinese intelligence services, alleged security vulnerabilities, and CCP narrative alignment, and their relationship to the broader data protection framework. Part IV addresses three evaluative questions. On the first question, whether DeepSeek responded adequately to regulatory demands, the evidence reveals a nuanced pattern best characterized as selective engagement: cooperative and expeditious remediation in South Korea (where the PIPC’s track record of muscular enforcement created credible consequences), but more reluctant and reactive accommodation in Europe (where the Italian ban remains in force one year later). Three factors help explain this asymmetry: differential enforcement leverage, structural accountability mechanisms, and market incentives. The article acknowledges, however, that DeepSeek did ultimately take meaningful remedial steps. The pattern might be characterized less charitably as forum-shopping, or more generously as rational prioritization by a resource-constrained startup facing simultaneous regulatory pressure across multiple jurisdictions. On the second question, the article distils lessons for both regulators and AI developers. For regulators: coordinated rapid response mechanisms prove valuable; the Article 27 representative requirement offers an important enforcement lever; extraterritorial enforcement faces structural limits when targets do not prioritize market access; direct-to-user warnings represent a legitimate but imperfect adaptation; and novel enforcement strategies (such as the Berlin DPA’s DSA Article 16 notices to Apple and Google) carry both promise and risk. For AI developers: regulatory precedents provide compliance roadmaps that should not be ignored; foundational compliance infrastructure must precede market entry; early cooperative engagement vastly outperforms reactive compliance; jurisdictional denials rarely succeed; and children’s data protections constitute non-negotiable red lines. On the third question, whether regulatory interventions constituted an effective brake on DeepSeek’s global adoption, the answer is starkly bifurcated. In the West, regulatory friction has kept DeepSeek’s market share low. Globally, however, downloads increased 960% in the nine months following the R1 release, and Microsoft research documents dominant market shares across China (89%), Belarus (56%), Cuba (49%), Russia (43%), and meaningful footholds across Africa (11–18%), with usage two to four times higher than in other regions. Several structural factors explain this asymmetry. The article situates these findings within the broader geopolitical context of US-China-EU technological competition. Europe deployed its most powerful regulatory tools against a Chinese AI provider, yet the practical effect of constraining DeepSeek in European markets may be to reinforce European dependence on American AI infrastructure rather than to advance European digital sovereignty. The irony deserves acknowledgment: European regulatory vigilance against a Chinese competitor clears competitive space for US platforms that have engaged more constructively with EU regulatory concerns. The article concludes that Western regulatory interventions, while successful in protecting European and other Western citizens from an AI service with documented compliance deficiencies, are structurally incapable of addressing the broader geopolitical challenge that DeepSeek represents. The episode tests—and finds wanting—fundamental assumptions underlying the European model of extraterritorial data protection enforcement: that market access to wealthy jurisdictions provides sufficient leverage to compel compliance; that actors who wish to offer services globally will ultimately submit to regulatory demands; and that the ‘Brussels Effect’ will operate as it has in other domains. DeepSeek’s first year demonstrates that a company can achieve massive global scale while explicitly claiming “it is not subject to European law”—not merely through defiance, but by serving the unregulated majority of the world’s population while treating Western markets as optional. The regulatory tools developed for an era of Western technological dominance may prove inadequate for a world in which competitive alternatives emerge from jurisdictions that do not share Western assumptions about privacy, transparency, or the relationship between technology companies and state power. The DeepSeek episode is not an endpoint but a harbinger, a preview of the governance challenges that will define the next decade of artificial intelligence development. Keywords: DeepSeek, AI, artificial intelligence regulation, GDPR, data protection, cross-border enforcement, AI governance, China, European Data Protection Board, extraterritorial jurisdiction, open-source AI, Global South, geopolitical competition, Brussels Effect |

One year ago, on January 27, 2025, the global technology landscape experienced what venture capitalist Marc Andreessen described as AI’s Sputnik moment. The Chinese artificial intelligence startup DeepSeek, founded in 2023 and headquartered in Hangzhou, released its R1 reasoning model, a large language model that claimed to match the performance of OpenAI’s o1 reasoning model and GPT-4o at a fraction of the cost. The company asserted that its model had been trained for a mere $5.6 million over two months, compared to the hundreds of millions typically invested by Western competitors. Within days of its release, the DeepSeek app surged to the top of the U.S. iOS App Store, surpassing ChatGPT.

The financial ramifications were immediate and severe. On what has since been termed “DeepSeek Monday” the U.S. stock market experienced one of its most significant technology-driven tumbles in history. Nvidia, the world’s leading AI chip manufacturer, saw its stock plummet by approximately 17%, wiping out nearly $589 billion in market value in a single trading session. The broader technology sector followed: Meta and Alphabet declined sharply, the Nasdaq fell by 3.1%, and the S&P 500 dropped by 1.5%. DeepSeek’s emergence fundamentally challenged the prevailing assumption that artificial intelligence supremacy required massive capital expenditures and access to the most advanced semiconductors, an assumption that had justified billions of dollars in infrastructure investments by Big Tech corporations such as Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. Developed using Nvidia H800 GPUs—chips specifically modified to comply with U.S. export restrictions—DeepSeek demonstrated that algorithmic efficiency could potentially offset hardware limitations, raising profound questions about the efficacy of U.S. chip export controls as a tool for maintaining technological advantage.

Beyond the market disruption, DeepSeek’s rapid global expansion triggered an unprecedented wave of regulatory scrutiny across multiple jurisdictions. Unlike previous AI deployments that attracted regulatory attention primarily from data protection authorities, DeepSeek’s emergence provoked responses from an unusually broad spectrum of governmental bodies spanning data protection authorities, national security agencies, cybersecurity regulators, and legislative bodies alike. Within days of the app’s viral adoption, concerns mounted regarding DeepSeek’s privacy policy, which candidly disclosed that user data would be stored on servers in China, and its apparent disregard for established data protection frameworks such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

The regulatory response to DeepSeek echoes, yet significantly amplifies, the experience of ChatGPT following its release in November 2022. When OpenAI launched ChatGPT, its privacy policy failures attracted immediate scrutiny from European data protection authorities. In March 2023, Italy’s Garante became the first Western country to impose a temporary ban on ChatGPT, citing violations of the GDPR including insufficient transparency regarding data processing, the absence of a valid legal basis for training algorithms on personal data, inaccuracies in outputs, and inadequate age verification mechanisms. That enforcement action served as a wake-up call to the AI industry. OpenAI ultimately cooperated with regulators, implemented remedial measures including enhanced privacy notices, opt-out mechanisms for training data, and improved transparency disclosures, and the ban was lifted within weeks. In December 2024, the Garante ultimately fined OpenAI €15 million for GDPR violations related to those early practices, a penalty the company has appealed, but which nonetheless established important precedents regarding regulatory expectations for AI providers operating in Europe.

Remarkably, despite the ChatGPT experience having provided clear regulatory guidance and lessons that should have served as a roadmap for subsequent AI deployments, DeepSeek appeared to launch in Europe and worldwide without incorporating any of these hard-won insights. The result, as we will see, has been a tsunami of reactions by Data protection Authorities in Europe and beyond.

Yet the regulatory concerns extended well beyond data protection. DeepSeek’s Chinese ownership and the potential for data sharing with Chinese government authorities under national security laws generated significant national security apprehensions. Multiple governments moved to restrict or ban DeepSeek on government devices and systems.

This article provides a comprehensive assessment of the global regulatory reactions to DeepSeek over the past year, examining responses from data protection authorities, national security bodies, and other relevant regulators. Part I surveys the reactions of data protection authorities in Europe and beyond, documenting the investigations, bans, and corrective measures imposed by regulators from Italy to South Korea. Part II unpacks the key data protection concerns raised by DPAs, analyzing the specific data protection problems at issue and the substantive legal questions regarding lawfulness, transparency, data transfers, and the rights of data subjects. Part III examines reactions from authorities focused on confidentiality, cybersecurity, and national security, including government device bans, legislative proposals, and the emergence of AI governance frameworks that extend beyond traditional data protection considerations. Part IV addresses three evaluative and extremely important questions: First, did DeepSeek respond adequately to regulatory demands, and has its engagement with regulators demonstrated a meaningful commitment to compliance with applicable legal frameworks? Second, what lessons can be drawn from the regulatory reactions to DeepSeek, both for regulators seeking to address cross-border AI deployments and for AI developers seeking to avoid similar enforcement actions? Third, and perhaps most practically significant, have these regulatory interventions constituted an effective brake on DeepSeek’s adoption worldwide, or has the Chinese AI startup continued to expand despite, or perhaps in some markets, because of, the global regulatory scrutiny it has attracted?

One year on from “DeepSeek Monday”, the answers to these questions carry implications not only for DeepSeek’s future but for the broader regulatory governance of artificial intelligence in an era of intensifying geopolitical competition over AI supremacy.

I. Reactions by Data Protection Authorities in Europe and Beyond

Since the launch of its R1 model, DeepSeek has faced a wave of scrutiny from data protection authorities across multiple jurisdictions. This section offers a mapping of some among the known reactions from data protection authorities (DPAs), particularly within the European Union but also beyond, highlighting the coordinated attention drawn by DeepSeek’s data processing practices. While this list may not be exhaustive, it captures the most prominent and publicized regulatory steps taken so far.

1) Reactions by DPAs in Europe

The release of DeepSeek-R1 triggered a cascade of regulatory interventions across Europe, marked by exceptional speed and a shift toward proactive enforcement. Within weeks of its debut, Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) in nearly every major EU jurisdiction initiated formal inquiries.

Italy: Garante Imposes Immediate Ban

On January 28, 2025, the Italian Data Protection Authority (Garante) became the first authority to send a request for information to DeepSeek. Garante contacted both Hangzhou DeepSeek Artificial Intelligence and Beijing DeepSeek Artificial Intelligence, the companies offering the DeepSeek chatbot service through web and app-based platforms. The authority sought information on several issues, including “which personal data are collected, the sources used, the purposes pursued, the legal basis of the processing, and whether they are stored on servers located in China.”

Following this request, a press release on Garante’s website stated that, on January 29, DeepSeek “declared that they had not entered and had not planned to enter the Italian market, as well as that they had removed the DeepSeek app from the [Italian] local app stores.” In the same response, the company also “claimed that the Regulation does not apply to the personal data processing activities carried out by them.”

Upon investigation, Garante found that the DeepSeek app was no longer available on local app stores. However, DeepSeek services were still accessible through the website and remained available to users who had previously registered. Thus, Garante stated that “it was confirmed that the Companies unquestionably offer the DeepSeek service to data subjects located in the European Union, more specifically in Italy, and therefore process the personal data of such data subjects.” As a result, DeepSeek was found prima facie to have failed to meet a series of GDPR obligations. Following these findings, on January 30, Garante imposed an immediate ban on DeepSeek in Italy, prohibiting the company from processing the data of Italian users. In addition to this order, the authority also launched a formal investigation.

Ireland: Data Protection Commission Requests Information

On January 29, 2025, the Irish Data Protection Commission (DPC) sent a request for information[i] to DeepSeek, seeking details on the data processing conducted in relation to data subjects in Ireland. As of now, there is no publicly available information on the follow-up to this request.

Belgium: Test Achats Files Complaint

On the same day, Testachats, a Belgian consumer organization, lodged a complaint against DeepSeek with the Belgian Data Protection Authority. Following the complaint, the Belgian authority confirmed that it had received the complaint but declined to provide further details at that time.

Greece: Homo Digitalis Urges Investigation

On January 30, 2025, Homo Digitalis, a Greek civil society organization, submitted a formal request to the Hellenic Data Protection Authority (HDPA), urging an investigation into DeepSeek over privacy concerns and data processing practices. Following this, on February 6, 2025, the HDPA launched an investigation into DeepSeek.

France: CNIL Analyzes DeepSeek

On January 30, 2025, Reuters reported that a spokesperson for the CNIL, the French data protection authority, stated that “the CNIL’s AI department is currently analysing this tool.” They also added, “In order to better understand how this AI system works and the risks in terms of data protection, the CNIL will question the company that offers the DeepSeek chatbot.”

Portugal: DECO Proteste Files Complaint

On January 31, 2025, DECO Proteste, a Portuguese consumer organization, filed a complaint about DeepSeek with the Comissão Nacional de Protecção de Dados (CNPD), the Portuguese data protection authority. The complaint highlighted concerns over DeepSeek’s data processing practices and potential violations of the GDPR.

Luxembourg: CNPD Expresses Concerns

On February 3, 2025, Luxembourg’s data protection authority, the National Commission for Data Protection (CNPD), stated in a press release that DeepSeek’s “use raises major concerns, particularly as regards the collection and processing of data without sufficient guarantees. Data entered by users in ‘prompts’ can be recorded, transferred, stored or analysed without a clear data protection framework.”

Spain: OCU Files Complaint

On February 3, 2025, the Spanish consumer organization OCU filed a complaint with the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD), alleging that DeepSeek committed multiple violations of the right to privacy under the GDPR. As a result, the organization requested that the AEPD intervene to regulate DeepSeek’s processing of personal data belonging to Spanish users.

Netherlands: AP Investigates Data Storage Practices

On February 3, 2025, the Dutch Data Protection Authority (AP) Chairman Aleid Wolfsen made a critical comment about the fact that the personal data of EU users, including prompts and documents uploaded into the DeepSeek chatbot, may be stored on a server in China, indicating that the Dutch DPA was also examining the issue.

Croatia: Requested Information from DeepSeek

On February 3, 2025, Euroactiv reported that the Croatian Data Protection Authority has requested information from Deepseek regarding it’s data processing practices.

Poland: UODO Conducts Analysis

On February 7, 2025, the Polish Personal Data Protection Office (UODO) stated in a press release that they were conducting an analysis of DeepSeek, including the fact that user data may be stored on servers located in China.

Lithuania: Recommends Exercising Caution When Using DeepSeek

On February 11, 2025, the Lithuanian State Data protection Inspectorate (VDAI) issued a press release advising citizens to exercise caution when using the DeepSeek app.

Germany: Berlin Commissioner’s Radical Move

On 14 February 2025, a coordinated investigation into DeepSeek’s data-processing practices was launched by several German data protection authorities. The investigation sought to determine DeepSeek’s compliance with the GDPR and to assess the potential risks posed by the chatbot. Subsequently, on 20 February 2025, the Hesse Data Protection Authority issued a public statement confirming the initiation of the investigation.

In Germany, the Berlin Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (BlnBDI) took an unusually “DSA-centric” step in the DeepSeek saga. After concluding that DeepSeek’s service processes extensive user data (prompts/chat histories, uploads, device/network and location data) and stores/transfers it to servers in China, the Berlin DPA asked DeepSeek on 6 May 2025 to voluntarily remove its apps from the German app stores, stop the allegedly unlawful data flows to China, or otherwise bring the processing into compliance with the GDPR’s third-country requirements.

When DeepSeek did not comply, the Berlin DPA escalated by sending DSA Article 16 “notice-and-action” notifications to the operators of the two largest app platforms, Apple and Google, on June 27, 2025, characterising DeepSeek as “illegal content” and urging the app stores to review the notice and decide whether to block the app in Germany. This step was taken in coordination with other German DPAs (Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Bremen) and after informing Germany’s Digital Services Coordinator at the Federal Network Agency. Apple and Google did not follow this non-binding requests and DeepSeek remains available in their App Stores in Germany.

The move matters well beyond DeepSeek because it tests whether DSA Article 16, typically used for straightforward categories of “illegal content,” can become a de facto enforcement lever for complex GDPR disputes – effectively pushing Apple/Google into a quasi-adjudicative role and risking single-market fragmentation if different national authorities “signal” illegality through non-binding notices. I have discussed this episode—and the major legal issues it raises—extensively in a separate article here.

EDPB broadens the scope of its ChatGPT task force to cover DeepSeek

In addition to the reactions from individual DPAs, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has announced on February 12, 2025, during its plenary meeting, the expansion of its ChatGPT Task Force into a broader AI Enforcement Task Force. This initiative aims to coordinate enforcement actions across EU member states, particularly concerning AI service providers [such as DeepSeek, not expressly stated by the EDPB] operating without a legal establishment within the EU. The EDPB also emphasized the necessity of a “quick response team” to address.

2) Reactions in South Korea

In parallel with the wave of regulatory scrutiny unfolding across Europe, South Korea also took swift action in response to the launch of DeepSeek’s chatbot service. While the country did not immediately impose a formal ban like Italy, its privacy regulator, the Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC), moved quickly to engage with the Chinese AI company amid growing concerns over its data practices.

Shortly after DeepSeek’s release in the South Korean market in January 2025, the PIPC initiated an inquiry into the company’s data collection and processing methods. Without a registered business representative in South Korea at the time, DeepSeek was contacted via email with a request for information regarding its data flows, legal basis for processing, and any potential transfers of user data overseas. Within days, the PIPC discovered that DeepSeek had transmitted personal data, including user prompts, to third-party entities, including ByteDance, without clear consent or appropriate disclosure.

In response, and following the regulator’s request, DeepSeek voluntarily removed its application from South Korean app stores on February 15. This measure, though not a ban, was presented as a temporary suspension of new downloads pending the resolution of identified privacy and data management issues. Existing users retained access to the service, but the PIPC emphasized that it was undertaking a preliminary fact-finding inspection under South Korea’s Personal Information Protection Act.

Public concerns escalated following confirmation that data had been transferred to foreign entities, and PIPC Chair Ko Hak-soo addressed the matter during a parliamentary hearing. He acknowledged that DeepSeek had responded promptly and cooperatively but stressed the seriousness of the issues uncovered. In the meantime, the company designated a local representative in South Korea and pledged to align its operations with domestic legal requirements.

On April 24, the PIPC publicly disclosed the results of its preliminary inspection. It identified several critical shortcomings in DeepSeek’s data processing practices, that will be discussed later in this article. As a result, the regulator issued formal corrective recommendations, ordering the company to delete previously transferred data, update its privacy policy, strengthen its security protocols, and establish a local legal presence.

DeepSeek accepted the recommendations and, on April 28, 2025, notified the PIPC of its compliance. The company resumed service in South Korea the same day, having updated its privacy policy to reflect South Korean legal standards and reintroduced its app to local download platforms. These recommendations now carry the force of binding corrective orders under Article 63-2 of the Personal Information Protection Act, and DeepSeek is required to submit a compliance report within 60 days. Follow-up inspections are also planned to monitor ongoing adherence to the new obligations.

* * *

The above mapping demonstrates the breadth and speed with which data protection authorities have reacted to DeepSeek’s global deployment. But what, precisely, triggered such widespread concern? In the next part of this article, we examine the specific data protection issues that were raised, ranging from opaque data transfers and inadequate user consent to questions about the lawful basis for processing and the rights of individuals under applicable privacy laws.

II. Unpacking the DPAs’ Key Data-Protection Concerns

Having mapped the rapid succession of regulatory reactions, we can now move from chronology of regulatory reactions to substance. Despite differences in procedure, questions, fact-finding, inspections, and (in some cases) provisional measures— DPAs’ positions clustered around five recurring concerns: (1) transparency and information duties; (2) cross-border data flows; (3) the use of personal data for model training; (4) safeguards for children; (5) territorial scope and EU representative obligations. As a result, some DPAs took the unusual step of issuing operational guidance to end-users (6). This part addresses each theme in turn se below, and explain why regulators in several jurisdictions considered DeepSeek’s approach difficult to reconcile with current data-protection requirements.

1) Opaque Processing Policies and Transparency Deficits

A first theme across several enforcement files was DeepSeek’s opacity: several regulators found that users could not understand what data were processed, for which purposes, on what legal bases, for how long, and with what practical avenues to exercise their rights. Transparency failures mattered not as “mere paperwork” issues, but as foundational defects capable of undermining the entire GDPR/PIPA/Data protection requierments architecture: if the information layer is incomplete or inaccessible, meaningful consent, valid reliance on alternative legal bases, and the effective exercise of rights all become illusory.

The Italian Garante’s early intervention illustrates this point. After sending a request for information on January 28, 2025, and receiving DeepSeek’s response on January 29 2025, the Garante adopted a position on January 30, 2025 which, among other issues, documented a set of transparency-related shortcomings. The authority noted that DeepSeek’s privacy policy (then “updated” as of December 5, 2024) was available only in English and did not comprehensively comply with the information duties under Articles 12–14 GDPR. It further criticised the policy for failing to specify, in a “granular” and service-specific way, the conditions of lawfulness for each processing activity (raising Article 6 GDPR concerns), and stressed that the lack of adequate information had direct consequences for the exercise of data-subject rights under Chapter III GDPR.

Within the European Union, several member states, including Ireland, Belgium, France, Croatia, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Poland, Lithuania, and Germany, initiated actions addressing transparency concerns surrounding DeepSeek (see Table 1 for a detailed overview of actions taken and their underlying reasons).

In the wake of these early EU interventions, DeepSeek revised and expanded its publicly available Privacy Policy to include jurisdiction-specific terms aimed at EU/GDPR compliance. An updated version dated February 14, 2025 already contained a dedicated “Supplemental Clause – Jurisdiction-Specific” for the European Economic Area (EEA), Switzerland and the UK, and the currently published policy states it was last updated on December 22, 2025. In this “European Region” notice, DeepSeek attempts to respond to key transparency criticisms by (i) mapping purposes to GDPR-style legal bases through a structured table (contract necessity, consent, legitimate interests, compliance with legal obligations), (ii) providing a more detailed rights catalogue (including access, rectification/erasure, restriction, portability, withdrawal of consent, objection, and the right to lodge a complaint with a DPA), (iii) explicitly flagging data storage in the People’s Republic of China, and (iv) identifying an EU/UK representative contact point (Prighter – see below) for data-subject requests.

[ South Korea’s Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC) reached analogous conclusions under the Personal Information Protection Act (PIPA). In its status examination, the PIPC explained that when [ DeepSeek entered the Korean market on January 15, 2025 its privacy documentation was available only in Chinese and English and failed to meet even the most basic disclosure duties set by South Korea’s Personal Information Protection Act.] The document omitted legally-mandated items such as the procedure and timeline for destroying personal data, a description of applicable safety measures, and the name and contact details of the company’s privacy officer; it also announced an extraordinarily broad collection of “keystroke patterns and rhythms” without explaining why such data were needed or how they would be safeguarded. The PIPC characterised these omissions as a transparency failure that left users unable to understand, let alone challenge, how their information was being handled.]

During the preliminary inspection DeepSeek submitted, on March 28, a Korean-language privacy policy and a jurisdiction-specific clause that finally set out the statutory items, legal basis, retention periods, destruction methods, data-protection officer details, and other disclosures, required under Korean law. The company also told investigators that references to keystroke monitoring had been drafted before the data-collection scope was finalised and confirmed that no such data had actually been gathered, revising the policy accordingly. Nonetheless, the PIPC concluded that the initial opacity was a serious breach and issued a corrective recommendation obliging DeepSeek to keep the full Korean policy publicly accessible and to “continue to ensure the transparency of its service” as a condition for resuming downloads.

2) Data flows to China

A second cluster of concerns related to where DeepSeek user data ended up, and under which legal conditions. Several authorities (and public warnings) framed the issue as one of personal data being sent to and/or stored in China without adequate safeguards, sometimes with an explicit emphasis on prompt content (not merely metadata) and on the risk of access by Chinese public authorities.

South Korea’s PIPC articulated the most granular factual narrative. In its preliminary inspection results published on April 24, 2025, the Commission reported that, initially, DeepSeek transferred personal information to multiple companies in China and the United States “for purposes such as service improvement [and] security” without obtaining user consent or disclosing the cross-border transfers in its processing policy. Public reporting, drawing on the PIPC’s statement, specified that the transferred data included device/network/app information and even the content of users’ prompts, routed (among others) to Beijing Volcano Engine Technology; DeepSeek justified this as a cloud/security and UI/UX measure, but the Commission considered the transfer of full prompt content unnecessary, and noted that DeepSeek blocked new transfers from April 10, 2025. The PIPC’s corrective recommendations also placed front and centre the need to ensure a legal basis for overseas transfers, destroy personal information already transferred, and improve transparency through Korean-language disclosures.

Within the EU, the same China-focused narrative quickly surfaced, often in simplified form, through early interventions and public communications. In Italy, the Garante’s inquiry (late January 2025) explicitly sought clarification as to whether personal data were stored on servers located in China, and DeepSeek’s replies were described as insufficient, prompting an immediate block and an investigation.

Luxembourg’s CNPD, in its February 3rd, 2025 recommendations, warned that data entered in prompts “can be recorded, transferred, stored or analysed” without a clear framework, linking this to broader concerns about governance, transparency, and the practical difficulty for EU individuals to exercise rights where the controller lacks an EU representative.

The Dutch AP likewise announced a broader investigation into transfers to China and warned users about uploading personal data (including third-party data) that could end up in China, underscoring that storage outside of the EU is only lawful under strict GDPR conditions.

The most legally explicit “transfer” framing, however, came from Berlin. In a press release of June 27 2025, the Berlin Commissioner stated that DeepSeek transfers personal data to “Chinese data processors” and stores it on servers in China, that the EU has no adequacy decision for China, and that DeepSeek had not provided “convincing evidence” of essentially equivalent protection. The statement expressly tied this to GDPR Article 46(1) and highlighted the risk landscape: “Chinese authorities have extensive access rights” and users purportedly lack enforceable rights and effective remedies. The Berlin DPA further noted it had requested compliance on May 6, 2025 and, after non-compliance, sent DSA Article 16 notices to Apple and Google on June 27, 2025 to trigger potential delisting in Germany.

In my separate analysis (published on the European Law Blog), I argue that a few DPA communications —especially Berlin’s— may be getting the “transfer” theory a bit wrong, at least as framed under GDPR Chapter V. The key point is definitional: not every cross-border data flow is a “transfer” for Chapter V purposes. The EDPB’s Guidelines 05/2021 set out a cumulative, three-part test and stress that where a non-EU controller directly collects data from EU users while targeting them under Article 3(2), this does not constitute a Chapter V transfer, the EDPB’s Example 1 states unambiguously that Chapter V “does not apply” in that scenario.

That conclusion does not “let DeepSeek off the hook.” If DeepSeek offers services to EU users, it may still be subject to GDPR duties via Article 3(2), including lawfulness and purpose limitation (Article 5), an appropriate legal basis (Article 6), transparency (Articles 12–14), security (Article 32), and the obligation to appoint an EU representative (Article 27). But it does mean that invoking Chapter V / Article 46(1) as the primary infringement hook is on thin ice in the direct-collection configuration, and that DPAs should be precise about which GDPR provisions are allegedly breached. The Garante, for instance, was much more precise here by statingthat DeepSeek was found to have stored data in the People’s Republic of China, “in violation of the safeguards provided by the Regulation, particularly Article 32 on the security of processing”.

3) Training the model: lawful-basis gaps in using user data and public web data

A third recurring concern, raised both in EU information requests and in South Korea, was whether DeepSeek’s model-development pipeline relied on (i) user-generated content (prompts, uploads, interactions) and (ii) publicly available web data gathered via scraping, without sufficiently clear disclosure, user control, and a defensible lawful basis for these distinct inputs.

In South Korea, the PIPC found that DeepSeek used two main categories of data for AI development and learning: publicly available data (including open-source and web-collected data) and users’ prompt inputs. Yet, at launch, the service offered no function allowing users to refuse the use of their prompt content for training, and the privacy documentation framed processing only in generic terms (“service provision and improvement”), which the Commission considered insufficient notice for such downstream use. In the PIPC’s view, this opacity, combined with the absence of an opt-out, undermined purpose limitation and informed choice under the Personal Information Protection Act for the prompt-data component of the training pipeline.

Following the PIPC’s inspection, DeepSeek reported that it implemented an opt-out function on March 17, 2025 enabling users to exclude prompt inputs from AI development and learning. It also pledged alignment with South Korea’s enhanced protection measures for major AI services (issued in 2024), which, among other elements, emphasise clearer disclosure of how training data are sourced and used, user choice mechanisms, and practical safeguards to prevent the ingestion of highly sensitive identifiers from online sources during pre-training. In its April 24, 2025 preliminary decision, the PIPC framed these steps as only a starting point: DeepSeek must demonstrate that the opt-out is effective, and that future model-development activities involving personal information (whether drawn from user interactions or otherwise) rest on a transparent and legally sustainable basis, failing which escalation remained on the table.

In the EU, the same “training inputs” issue surfaced immediately, and explicitly included web scraping. On January 28, 2025, the Italian Garante’s first information request asked not only what personal data DeepSeek collects and for which purposes, but also what information is used to train the AI system, and, in particular, whether personal data are collected through web scraping activities.

In its current Privacy Policy (Last Update: December 22, 2025), DeepSeek is more explicit that it uses personal data “to improve and develop the Services and to train and improve [its] technology,” and it expressly adds that it may obtain “Public Personal Data” via online sources to train [its] models and provide Services. The policy also contains an EEA/Swiss/UK supplemental clause that, for the “train and improve our technology” purpose, attempts to map processing onto GDPR-style legal bases, primarily legitimate interests (with a generic reference to aggregation/anonymisation and privacy-by-design) and, in some cases, consent “when we ask for it.” However, it does not clearly provide an EU-facing opt-out specifically for training (or a granular mechanism for refusing prompt re-use for model development), beyond general rights language such as the right to object where legitimate interests are relied upon. Nor does it meaningfully detail how “online sources” are collected (including scraping), which sources/categories are used, or what concrete safeguards/filters are applied, the very issues EU DPAs were already probing (notably the Garante’s web-scraping question).

4) Children’s data and safety

A fourth recurring concern centred on minors’ data and, more broadly, the safety architecture of the service. Regulators framed children’s safeguards as a core compliance requirement, given the heightened legal protections applicable to minors and the practical likelihood that popular chatbots will be used by under-age users unless robust barriers exist.

In South Korea, the PIPC found a clear mismatch between DeepSeek’s stated policy and its operational reality. DeepSeek’s terms indicated that users under 14 were not permitted, yet at launch the service had no age-verification procedure at sign-upand no technical barrier preventing children from opening accounts. The Commission therefore viewed any collection of minors’ personal information as effectively uncontrolled, and potentially unlawful under the PIPA’s enhanced rules for children, especially because the privacy documentation did not clearly explain how children’s data would be detected, handled, or deleted if ingested. During the inspection, DeepSeek implemented an age-verification procedure, and the PIPC’s April 24 2025 preliminary findings required the company to (i) determine whether it had in fact collected any under-14 data, (ii) erase such data immediately if present, and (iii) demonstrate, through documentation and follow-up testing, that the age-gate is fully operational and kept under continuous review through post-remediation checks.

The PIPC also linked “children’s data” concerns to a wider service-safety baseline. In the same set of findings, it recorded that certain security vulnerabilities had been identified and that remedial measures were completed during the inspection (including issues such as access controls around development environments). This underscores an important enforcement intuition: where minors may access a service, weaknesses in age controls and weaknesses in security governance become mutually reinforcing risk factors, both of which can heighten the likelihood and impact of unlawful processing.

Within the EU, concerns about protective measures for minors were also raised early, including through private enforcement triggers. In Belgium, the consumer organisation Testachats/Test-Aankoop filed a complaint on January 29, 2025, which (as reported publicly) included allegations relating to inadequate protections for minors; the Belgian Data Protection Authority reportedly opened a formal investigation the following day.

5) Missing legal representative: territorial compliance failures and accountability gaps

A fifth, and highly practical, fault line concerned territorial compliance via a designated legal representative, i.e., whether DeepSeek had put in place a legally accountable in-country / in-region contact point enabling regulators and individuals to serve notices, exercise rights, and obtain effective redress. Several authorities treated the absence of such a representative not as a technicality, but as a structural obstacle to enforcement and user recourse, and, in turn, as an indicator that DeepSeek entered regulated markets without basic compliance scaffolding.

South Korea: lack of a domestic representative as an early “launch without compliance”

In South Korea, the PIPC documented that shortly after the service’s domestic launch, its office sent DeepSeek a formal inquiry on January 31, 2025, amid immediate concerns about “domestic and international privacy violations,” and the Commission proceeded to a preliminary inspection that also focused on DeepSeek’s ability to engage with Korean authorities. Public reporting on the PIPC’s process further highlighted that DeepSeek appointed a local representative in the course of the Korean proceedings and acknowledged that it had partly neglected to consider Korean legal requirementswhen launching globally. The PIPC’s April 2025 preliminary decision then made continued compliance, supported by in-country agentsandfollow-up inspections at least twice a year, part of the broader corrective framework through which DeepSeek’s ongoing adherence would be monitored.

European Union: Article 27 GDPR as a recurring enforcement lever

Within the EU, multiple interventions likewise foregrounded the absence (initially and for several months) of an EU representative under Article 27 GDPR. Luxembourg’s CNPD stated bluntly on February 3rd ,2025 that the lack of a DeepSeek representative in the EU “creates legal uncertainty” and makes it “difficult, if not impossible” for individuals to exercise GDPR rights; it also warned that the absence of an EU representative renders cooperation with DPAs uncertain and “any regulation or recourse … particularly complex.”

Germany’s authorities went further still by coordinating an inter-Länder audit explicitly aimed (at least initially) at verifying whether DeepSeek had appointed an EU representative. DataGuidance reported that German DPAs launched a coordinated investigation in February 2025 focused on compliance questions surrounding DeepSeek, including the Article 27 representative obligation. Separate reporting likewise noted that the absence of an EU representative meant that multiple DPAs could proceed in parallel (given the lack of a one-stop-shop anchor).

Italy’s Garante also treated the missing representative as part of the overall compliance failure picture in its DeepSeek file, with law-firm reporting on the January 30, 2025 measure noting, among the authority’s concerns, failures relating to transparency and to key GDPR compliance obligations (including representative-type accountability gaps).

Finally, the Greek (Hellenic) DPA appears to have played a catalytic role in moving DeepSeek from “no representative” to formal Article 27 compliance. According to multiple public trackers and reports, following the HDPA’s interim steps (including Interim Ruling 18/2025 of May 21, 2025), DeepSeek informed the authority on May 28, 2025 that it had appointed Prighter EU Rep GmbH (Vienna) as its EU representative; the HDPA then closed the representative-focused investigation on May 29, 2025.

As a conclusion, across jurisdictions, the “representative” issue functioned as a proxy for something deeper: whether DeepSeek had built the minimum institutional interface required for legality, a reachable, accountable entity within the territory. That interface is what turns abstract rights and supervisory powers into something operational; without it, both enforcement and data-subject remedies risk becoming largely theoretical.

6) A notable twist: DPAs warning end-users directly

A striking feature of the DeepSeek episode is that several authorities did not confine themselves to the “classic” enforcement toolkit, information requests to the controller, inspections, corrective measures, and (where warranted) bans. Instead, they also spoke directly to the public, issuing practical user-facing warnings: don’t install, don’t input personal/confidential data, think twice before uploading data about third parties, and prefer compliant tools. This is unusual in tone and posture. It reflects a perception of immediate, hard-to-mitigate risk, coupled with enforcement friction (a non-EU actor, uncertain cooperation, limited leverage, and the speed of viral adoption). It also subtly shifts part of the risk-management burden onto users.

Luxembourg (CNPD) is a clear example of this “direct-to-user” approach. In recommendations published on February 3, 2025, the CNPD warned that data entered in prompts may be “recorded, transferred, stored or analysed” without a clear framework, and it offered concrete guidance: avoid installing the model/config files in IT environments, never enter personal or confidential data when using the online interface, raise awareness among employees and users, and favour AI tools that comply with the GDPR/AI Act and offer clear security/privacy guarantees. The CNPD explicitly connected this to enforceability: because DeepSeek was not established in the EU and had not appointed an EU representative, cooperation and effective rights exercise could be “difficult, if not impossible.”

Poland (UODO) adopted similarly cautionary language. On February 7, 2025, the President of UODO recommended “extreme caution” when using DeepSeek services, pointing (among other elements) to indications that user data may be stored on servers in China, again in a format aimed less at doctrinal GDPR debate than at immediate user risk awareness.

The Netherlands (AP) took the user-warning logic one step further by explicitly flagging the third-party data problem, and the possibility that the user can become the vector of illegality. Dutch reporting quoting AP Chair Aleid Wolfsen captured the message bluntly: users should ask themselves whether they really want to input personal/sensitive information; and if they upload other people’s data, it may end up in China without those individuals’ knowledge or consent, raising the spectre of user responsibility/liability for an unlawful disclosure. Reuters also reported that the AP coupled this warning posture with the announcement of a broader investigation.

The Lithuanian Data Protection Authority, the State Data Protection Inspectorate (VDAI), issued a warning on February 11, 2025 regarding the use of the DeepSeek application due to unresolved concerns about its compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The VDAI urged residents either not to use the application or to exercise extreme caution by avoiding the entry of sensitive personal data, whether relating to themselves or to third parties.

The Hessian Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (HBDI) adopted a technology-neutral, cautionary approach without expressly naming DeepSeek. In guidance issued on February 20, 2025, the HBDI advises users to exercise particular caution when deploying AI applications from providers established outside the EU or in countries without an EU adequacy decision, while formally leaving the final decision on use to organisations and individual users. It recommends selecting only transparent providers that can demonstrate compliance with the GDPR, refraining from entering personal or confidential data into online AI tools unless effective safeguards against misuse are clearly established, and verifying whether non-EU providers acting as controllers have appointed an EU representative pursuant to Article 27 GDPR. The HBDI further emphasises the need to actively train and sensitise staff and users to AI-related risks, including permissible data use, the correct interpretation of AI outputs, and the legal and ethical consequences of misuse.

* * *

The synthesis of these investigations reveals that the regulatory pushback against DeepSeek was not merely a set of disconnected administrative hurdles, but a collective forensic exposure of a fundamental architectural mismatch. While DeepSeek attempted to rectify its “launch-first” approach throughout 2025, retrofitting jurisdiction-specific supplemental clauses, appointing legal representatives like Prighter in Europe, and finally implementing opt-outs for training, these measures often appeared as reactive attempts to bridge an inherently wide gap.

The recurring themes of extraterritorial data flows to China and the lack of transparent “privacy by design” represent a structural barrier that supplemental policies may struggle to overcome. The unprecedented pivot of authorities toward issuing direct-to-user warnings underscores a growing regulatory conviction: when it comes to non-Western AI models operating outside of adequacy decisions, the burden of risk management is increasingly being shifted from the state to the individual.

III. Reactions by Other Authorities Focused on Confidentiality, Cybersecurity and National Security Concerns

While Part I and II of this article analyzed the procedural and rights-based friction between DeepSeek and global Data Protection Authorities (DPAs), this section explores a far more consequential regulatory theatre: the “hard edge” of national security and state power. For defence agencies, intelligence services, and executive ministries, the DeepSeek-R1 rollout was not merely a debate over privacy notices, but an operational security issue. Moving beyond the “notice-and-comment” framework of data protection, some of these authorities treated DeepSeek as a potential Trojan horse for asymmetric espionage by the Chinese Communist Party and a “five-alarm national security fire.”

1) The United States: A Total Defence Strategy

The United States government executed the most aggressive and multi-layered prohibition strategy globally. The US response was characterized by a “whole-of-government” approach, wherein military, intelligence, civilian federal agencies, and state governments acted in rapid succession to neutralize the perceived threat.

A. Federal Defence and Intelligence Agency Actions

The US military establishment identified DeepSeek not as a commercial tool, but as an operational security (OPSEC) vulnerability. The speed of the Pentagon’s response highlights the integration of AI software vetting into national defence protocols.

The Department of the Navy

On January 24, 2025, the United States Navy became one of the first global entities to issue a formal directive against the platform. In a memorandum distributed to the operational fleet and shore commands, the Navy prohibited the use of DeepSeek’s AI models “in any capacity.” The language of this directive was notably absolute. Unlike previous bans on social media apps which often focused on government-furnished equipment (GFE), the Navy’s order explicitly instructed service members to refrain from using the AI for “any work-related tasks or personal use.” This extension to personal use -when related to work tasks- reflects a recognition that data spillage can occur even via personal devices if the user is processing unclassified but sensitive operational details. The rationale cited “potential security and ethical concerns associated with the model’s origin and usage,” establishing a precedent that the software’s provenance alone was sufficient grounds for exclusion.

The Department of Defence (The Pentagon)

Following the Navy’s lead, the Defence Information Systems Agency (DISA), the combat support agency responsible for the DoD’s IT infrastructure, implemented a network-level blockade. Beginning January 28, 2025, DISA blocked access to DeepSeek domains across the Pentagon’s Non-Classified Internet Protocol Router Network (NIPRNet). This technical control was precipitated by internal audits which revealed that DoD employees had already utilized the chatbot for approximately two days prior to the ban. The rapid adoption by staff demonstrated the high utility of the tool and the necessity for immediate technical interdiction to prevent the ingestion of defence-related data into Chinese servers.

B. Civilian Federal Agency Prohibitions

Civilian agencies managing critical infrastructure, aerospace technology, and legislative affairs moved quickly to align with the defence sector, citing data privacy and the risk of intellectual property theft.

National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)

On January 31, 2025, NASA’s Chief AI Officer issued a memorandum titled Prohibiting the Use of DeepSeek Products and Services. This directive was highly specific, prohibiting personnel from using DeepSeek to “share or upload agency data” or accessing the service via any NASA-managed network connection. The memo highlighted the dual risk of data exfiltration and network compromise. Given NASA’s reliance on cutting-edge computational research, the agency also restricted the use of DeepSeek’s “services,” implying that even API-based integrations were forbidden. The prohibition was framed as a necessary step to protect “NASA’s data and information,” reflecting the high value of aerospace R&D to foreign competitors.

The Department of Energy (DOE)

The Department of Energy, which oversees the US nuclear arsenal and national laboratories, issued guidance requiring “heightened scrutiny” of AI platforms. This guidance was interpreted strictly by constituent research institutions. For example, the University of Idaho, acting on DOE requirements, issued a ban on August 7, 2025, stating that DeepSeek’s LLM and related products were “strictly prohibited on all DOE-owned devices.” Crucially, this ban extended to “downloadable ‘open weights’ AI models.” This is a critical distinction; unlike web-based bans that stop data from flowing out, the DOE ban recognized that the model itself, running locally, could pose risks through inherent vulnerabilities or licensing terms that might compromise federally funded research integrity.

The Legislative Branch: US House of Representatives

The Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) of the House of Representatives issued a notice on January 30, 2025, effectively banning the application for legislative staff. The notice warned that DeepSeek was “currently unauthorized for official House use” and provided a stark cybersecurity warning: “threat actors are already exploiting DeepSeek to deliver malicious software and infect devices.”

C. Federal Legislation: The “No DeepSeek” Act

To codify these agency-specific actions into permanent federal law, a bipartisan bill was introduced on February 7, 2025, by Representatives Josh Gottheimer and Darin LaHood, both members of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. The bill was entitled the “No DeepSeek on Government Devices Act.” It directs the Office of Management and Budget to develop standards requiring the removal of DeepSeek from all federal agency information technology. In his statement supporting the bill, Rep. Gottheimer characterized the app as “a five-alarm national security fire”, claiming that “we have deeply disturbing evidence that [the Chinese Communist Party is] using DeepSeek to steal the sensitive data of U.S. citizens”. At the time of the writing of this article this bill has not yet passed.

D. State-Level Executive Orders and Directives

The response from US state governments was characterized by a high degree of technical specificity and rapid executive action. State Chief Information Officers (CIOs) and Governors utilized emergency powers to secure state networks, often moving faster than the federal bureaucracy.

Virginia: The Model Executive Order

On February 11, 2025, Governor Glenn Youngkin signed Executive Order 46, titled Banning the Use of DeepSeek Artificial Intelligence on State Government Technology. This order serves as a primary case study for state-level bans due to its detailed justification.

The order explicitly cited security research indicating that the DeepSeek application “contains code capable of transmitting user login information to China Mobile, a state-owned telecommunications company banned from operating in the U.S..” The order further noted that the application disables encryption on certain Apple devices, leaving data vulnerable to interception. The ban applies to all state agencies, boards, commissions, and, crucially, public universities. It prohibits downloading or using the app on any state-owned device or wireless network.

Oregon: The Biometric Threat Analysis

The Oregon Department of Administrative Services (DAS) issued a memorandum on February 12, 2025, which ordered the immediate blocking of DeepSeek on state resources. The Oregon memo identified a specific, invasive data collection practice: the harvesting of “keystroke patterns and rhythms.” This biometric data could be used to fingerprint users behaviourally, a capability with profound counter-intelligence implications. The state CIO also noted that all data is stored on servers in the PRC, where government authorities can access it under Chinese law. The order required the blocking of the download of the application and the restriction of access through “multiple security points” on the state network.

List of Other State Actions

The table below summarizes the actions taken by several other states, demonstrating a nationwide consensus. It is based in the information provided here.

| State | Action Type | Date (approx.) | Specific Rationale or Scope |

| Texas | Executive Order | Feb 2025 | Blocked on government-owned devices; “China Nexus” risks. |

| New York | Statewide Ban | Feb 2025 | Connection to foreign government surveillance; ban on ITS-managed devices. |

| Tennessee | Governor’s Order | Mar 6, 2025 | Banned alongside Alibaba-owned Manus. |

| Arkansas | Governor’s Announcement | Mar 6, 2025 | Banned alongside RedNote and Lemon8. |

| Alabama | Agency Memo | Mar 26, 2025 | Classified as “harmful technology.” |

| Kansas | Legislation | Apr 8, 2025 | Bill approved banning it on state-owned devices/networks. |

| Georgia | GEMHSA List Update | Feb 2025 | Added to “Banned Platforms List” alongside other Chinese apps. |

| Nebraska | Executive Order | Feb 2025 | Ban on applications owned by affiliates of the CCP. |

2) Actions in the Asia-Pacific Region

For some democracies of the Indo-Pacific, the emergence of DeepSeek was perceived as a challenge to national information security in a region already defined by intense cyber-rivalry.

South Korea

In South Korea, beyond the actions of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC), based on data protection concerns and already analysed in detail above, other actors also moved to suspend the use of DeepSeek. Thus, even prior to the PIPC’s suspension, key ministries had erected firewalls. The Ministry of the Interior and Safety, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of National Defense, and the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy all blocked access to the platform.

Also, as MLex reports[ii], on February 9, 2025, South Korea’s spy agency, the National Intelligence Service, stated that DeepSeek was collecting personal information on an excessive scale, using all the data entered by users to train its AI model, sharing user data with advertisers without limitations and storing user data on offshore servers. “Unlike other generative AI services, [DeepSeek] was found to collect identifiable user information such as keyboard-typing patterns while being capable of transmitting chat records through communication functions to servers owned by Chinese companies, including volceapplog.com” the agency said.

Major South Korean conglomerates and other companies often aligned with government policy, with companies like Samsung and LG restricting use on corporate networks.

India

The Department of Expenditure (Ministry of Finance) issued an office memorandum (circular) on January 29, 2025. The circular explicitly stated: “It has been determined that AI tools and AI apps (such as ChatGPT, DeepSeek etc.) in the office computers and devices pose risks for confidentiality of Govt. data and documents… It is, therefore, advised that use of AI tools/AI apps in office devices may be strictly avoided.” While the circular mentioned ChatGPT, the timing and the specific inclusion of DeepSeek coincided with advisories from the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In) regarding the adversarial threats of AI applications.52 The directive acts as a binding instruction for the vast Indian bureaucracy.

Despite this, the Union Electronics and IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said that DeepSeek, being an open-source model, could be hosted on Indian servers after undergoing security-protocol checks so that users and developers could benefit from its code.[iii]

Against this background, two lawyers filed on February 19, 2025 a Public Interest Litigation in the Delhi high court concerning DeepSeek.[iv] In their petition, lawyers Bhavna Sharma and Nihit Dalmia, argue that DeepSeek is breaching national data privacy laws and poses “instant and emergent threats that are prejudicial to the sovereignty and integrity of India, the data security of the State, and public order.” The PIL requests from the courts a complete ban on DeepSeek in India. A division bench of the Delhi High Court asked in October 2025 “how the central government intends to address the platform’s security and privacy risks” and has listed the matter to be heard alongside other issues addressing similar AI-related issues, while awaiting the government’s detailed action plan.[v]

Australia

On February 25, the Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs in Australia issued a directive prohibiting the use of all DeepSeek products, applications, and web services on Australian Government systems. The decison requires all non-corporate Commonwealth entities to “identify and remove all existing instances of DeepSeek products, applications and services on all Australian government systems and mobile devices”. The entities also have to “prevent the access, use or installation of DeepSeek products, applications and services on all Australian government systems and mobile devices”.

Several Australian enterprises, including Optus, TPG Telecom, and Telstra, subsequently announced similar bans on the use of DeepSeek on their work devices. According to Sky News Australia: “The moves by leading companies come after Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke issued a statement about risks the Chinese AI posed to Australia’s security when he announced the government was banning DeepSeek”. Australian Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke stated, “AI is a technology full of potential and opportunity – but the Government will not hesitate to act when our agencies identify a national security risk.”

Japan

According to a report by The Asahi Shimbun on February 7, 2025, the Japanese government restricted ministries and agencies from using the DeepSeek chatbot due to concerns over its handling of personal data. Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi emphasized that “related ministries and institutions specializing in this issue will work together to address AIs, including DeepSeek.” Following this announcement, major Japanese firms Toyota Motor Corp and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. banned the use of DeepSeek by their employees, citing concerns over the technology’s data security. Japanese giant SoftBank Corp. also joined the growing number of Japanese companies banning access to DeepSeek on company devices.

3) Actions in Europe and Canada

In Europe and Canada, the security response was anchored in the “precautionary principle”, focusing on the integrity of federal infrastructure and the protection of civil service data. By leveraging cybersecurity agencies, these jurisdictions moved to pre-emptively scrub DeepSeek from government devices, framing the tool as incompatible with the security baselines required for official state business.

Belgium

Belgium implemented a strict prohibition of DeepSeek for its federal workforce. The ban was ordered by Vanessa Matz, the Minister of Government Modernisation, effective February 2025. All federal public administration employees were ordered to uninstall DeepSeek applications from work devices. The decision was based on a risk assessment by the Centre for Cybersecurity Belgium (CCB). Minister Matz described the ban as “preventive,” stating, “Trust in the government rests on fundamental principles of prevention… By banning the use of this system, we are demonstrating vigilance.”

The Netherlands

The Dutch government moved to protect its civil service from foreign intelligence gathering. The government formally banned civil servants from using DeepSeek on government devices. The Dutch justification explicitly cited “espionage concerns”. The Dutch data protection authority (AP) and government officials warned that the Chinese government could potentially access data stored on DeepSeek servers, posing a direct threat to state secrets.

Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic the National Cyber and Information Security Agency (NUKIB) issued a formal “Warning” regarding DeepSeek products.41 Under the Czech Act on Cyber Security, such a warning legally obligates operators of critical information infrastructure to conduct risk assessments and implement countermeasures. Following the warning, the Czech government approved a resolution banning the use of DeepSeek in state administration. The NUKIB warning was detailed, referencing China’s National Intelligence Law and the “unverifiable handling of data”. It categorized the use of DeepSeek as a “cyber security threat”, noting that data transfer to the PRC creates an exposure vector for state coercion.

Denmark

Denmark also took action against DeepSeek. On March 4, the Danish Parliament announced in a press release that it had imposed a ban on the use of DeepSeek on all work devices issued by the institution, including iPhones, iPads, and PCs. The decision was driven by concerns over potential surveillance risks involving parliamentary data.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom adopted a risk-management approach rather than a blunt legislative ban. The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) issued guidance stating that the use of DeepSeek is a “personal choice” for the public but warned of significant risks. The NCSC explicitly highlighted that “data inputted into the model will be sent to China and thus is subject to Chinese law”. While there was no “ban memo” publicized akin to other countries, the UK government’s policy dictates that “classified or sensitive data” cannot be processed on unvetted tools. Some departments nonetheless moved to explicit restrictions: the Department for Work and Pensions’ updated acceptable-use policy (reported 16 May 2025) continued to permit some LLM use on DWP devices but expressly prohibited access to DeepSeek.

Canada

Canada’s response was driven by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS), acting as the central employer and IT manager for the federal public service. On February 7, 2025, the Chief Information Officer of Canada, Dominic Rochon, issued a directiverecommending that all departments and agencies restrict the use of the DeepSeek chatbot. Shared Services Canada (SSC), which manages the IT infrastructure for 43 federal departments, immediately implemented the restriction on all mobile devices under its control. The Treasury Board framed the decision as a “precautionary measure” driven by “serious privacy concerns associated with the inappropriate collection and retention of sensitive personal information”. British Columbia moved in tandem with the federal government, banning the application for public sector staff.

IV. The Reckoning: Compliance, Lessons, and the limits of Regulation

On the basis of the previous analysis, we will address here three evaluative and extremely important questions.

1) Did DeepSeek Respond Adequately to Regulatory Demands?

The evidence assembled across this article reveals a striking asymmetry in DeepSeek’s engagement with regulators, one marked by initial defiance, gradual accommodation, and ultimately a tale of two regulatory theatres in which the company proved far more responsive to South Korean authorities than to their European counterparts.

At launch, DeepSeek’s regulatory posture was nothing short of defiant. The company’s privacy policy contained no mention of the GDPR or equivalent data protection frameworks in other jurisdictions, offered no adequate legal basis for transfers of personal data to China, provided no meaningful mechanisms for exercising data subject rights, and included insufficient safeguards for minors. When Italy’s Garante, the first Western authority to act, requested information about DeepSeek’s data practices on January 28, 2025, the company’s response was deemed “totally insufficient”. More remarkably still, DeepSeek went so far as to assert that EU law did not apply to its operations, position that regulators swiftly and unanimously rejected. This posture was all the more striking given that the ChatGPT precedent of 2022/2023, rather than serving as a cautionary example to be heeded, appeared to have been entirely disregarded.

The contrast with OpenAI’s response to the Garante’s enforcement action in March 2023 is instructive. When faced with a temporary ban and a twenty-day deadline, OpenAI engaged constructively: it cooperated with regulators, implemented enhanced privacy notices, introduced opt-out mechanisms for training data, improved transparency disclosures, and had the ban lifted within weeks. That experience provided a clear regulatory roadmap for any AI provider seeking to operate in Europe: engage promptly, provide comprehensive information, acknowledge the applicability of local law, and demonstrate a commitment to compliance through concrete remedial measures. DeepSeek, launching nearly two years later, had every opportunity to learn from this template. Instead, it replicated, and in some respects exceeded, OpenAI’s initial privacy failures while eschewing the cooperative engagement that had enabled ChatGPT’s rapid rehabilitation.

A. The European Theatre: Reluctant and Reactive Engagement

In Europe, DeepSeek’s path toward compliance has been slow, reluctant, and driven primarily by regulatory pressure rather than proactive initiative. The company’s initial position, that the GDPR simply did not apply to it, set the tone for what would prove to be a consistently reactive posture. Only after investigations proliferated across multiple Member States did DeepSeek begin to retrofit compliance measures onto its operations.

The timeline of DeepSeek’s policy updates illustrates this pattern. The company’s original privacy policy, dated December 5, 2024, was available only in English and contained no jurisdiction-specific provisions for European users. It was not until February 14, 2025 (more than two weeks after the Garante’s ban) that DeepSeek published an updated privacy policy containing a dedicated “Supplemental Clause, Jurisdiction-Specific” for the European Economic Area, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. This supplement attempted to address key transparency criticisms by mapping purposes to GDPR-style legal bases, providing a more detailed rights catalogue, explicitly flagging data storage in China, and identifying an EU representative contact point. Yet these measures, while representing progress from the complete absence of any GDPR acknowledgment, came only after DeepSeek had already been banned in Italy and faced active investigations in multiple other jurisdictions.

The appointment of an EU representative under Article 27 GDPR, a fundamental compliance obligation for non-EU controllers offering services to EU residents, proved even more protracted. Multiple DPAs flagged this deficiency from the outset, with Luxembourg’s CNPD stating bluntly in February 2025 that the absence of a representative “creates legal uncertainty” and makes it “difficult, if not impossible” for individuals to exercise their GDPR rights. Yet DeepSeek did not appoint an EU representative until May 28, 2025, fully four months after the Italian ban, and only after the Greek Hellenic Data Protection Authority issued Interim Ruling 18/2025 on May 21, 2025, ordering the company to designate a representative. The company ultimately appointed Prighter EU Rep GmbH, a Vienna-based firm, as its EU representative, a step that should have been taken at launch, not five months into a compliance crisis.

Perhaps most telling of DeepSeek’s European engagement deficit is the Berlin Commissioner’s escalation in June 2025. After requesting compliance on May 6, 2025, and receiving no satisfactory response, the Berlin DPA took the unprecedented step on June 27, 2025 of sending DSA Article 16 “notice-and-action” notifications to Apple and Google, characterizing DeepSeek as “illegal content” and urging the app stores to review whether to block the app in Germany. That a European DPA felt compelled to invoke the Digital Services Act’s notice mechanism, effectively asking private platforms to adjudicate a complex GDPR dispute, speaks volumes about the limits of DeepSeek’s engagement with European regulators. As of the time of writing, Italy’s ban remains in force, Germany’s enforcement continues, and DeepSeek’s substantive compliance with European data protection requirements remains a subject of ongoing investigation and considerable doubt.